081: How can I decide which daycare/preschool is right for my child?

I regularly receive questions from listeners asking me whether they should put their child in daycare or preschool and my response has typically been that there isn’t a lot of research on the benefits and drawbacks for middle class children on whether or not the child goes to daycare/preschool, and that is still true. I’ve done research on my listeners and while parents of all types listen to the show, the majority of you are fortunate enough to not be highly economically challenged.

So in this episode we’ll talk about why preschool is considered to be such a good thing for children of lower-income families, and also what research is available on the effects – both positive and negative – of daycare and preschool on children of middle- and upper-income families.

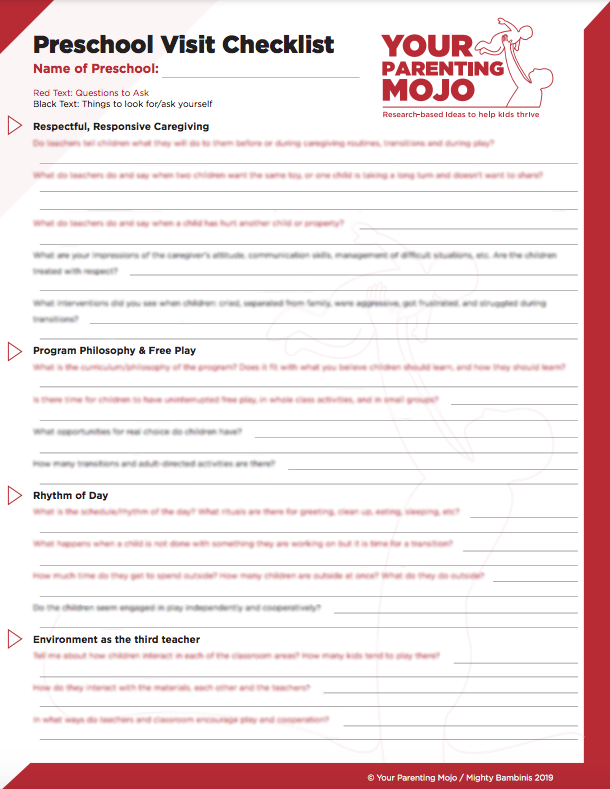

You’ll also hear me mention in the show that it’s really, really difficult even for researchers to accurately measure the quality of a daycare/preschool setting because you can’t just get data on child:teacher ratios and teacher qualifications to do this. You have to actually visit the setting and understand the experience of the children to do this – but what do you look for? And what questions do you ask? In the show I mention a list of questions you can ask the staff and things you can look out for that Evelyn Nichols, M.Ed of Mighty Bambinis and I put together – Click here to download.

Let me know (in the comments below) if you have follow-up questions as you think through this decision for your family!

Hello and welcome to the Your Parenting Mojo podcast. Today we’re covering an altruistic episode – one that I don’t need, because we already made this decision a long time ago – and that’s on how to decide whether you should put your child in daycare or preschool. I regularly get questions from listeners on this and my response has typically been that there isn’t a lot of research on the benefits and drawbacks for middle class children on whether or not the child goes to daycare, and that is still true. I’m going to be really up-front here and say that the vast majority of the literature related to childcare is conducted from the perspective of looking at methods to close the enormous deficit in skills – particularly language skills – with which poor children, and particularly poor Black children, enter kindergarten. Yet very, very few of these researchers ever think to question the system in which this research, and the poor children themselves, reside – these children only have a “deficit” of skills because the school system isn’t set up to value and develop the skills these children DO bring. So the vast majority of this research says something along the lines of “poor children have X, Y, and Z skills when they enter daycare, and daycare has success at closing the X gap between poor children and middle class children but not Y and Z.”

Now I’ve done research on the listeners of this show and while there are certainly parents of all kinds listening, I think my listeners – and certainly the people who email me asking about daycare – are mostly fortunate enough to not be highly economically challenged. Many of them have been stay-at-home parents for several years and are trying to decide whether the child would benefit more from continuing to stay home or go to daycare, rather than making this decision from the perspective of “our family needs another income so my child is going to have to go to daycare,” although there are a few who worry about whether they are somehow being selfish for wanting to work and sending their child to daycare. So we should acknowledge that the concerns of parents who are asking me about daycare and preschool for their children are pretty different from those of most of the researchers who look at this question. But there are some researchers who have taken a different perspective, or who have looked at the data in such a way that allows us to understand more about how this decision affects our children, so today we’re going to look at the what the scientific literature says on this topic. We’ll look at whatever research is available in the pre-kindergarten years, so throughout this episode when I say “daycare” I mean care for infants, and when I say “preschool” I mean care for toddlers and up, and I’ll let you know the age group that the studies refer to.

And I have a couple of other treats lined up for you as well. If you’re in the U.S. and possibly some other Western countries as well you may be gearing up for preschool touring season so my friend Evelyn Nichols, who used to run the RIE- and Reggio Emillia-inspired daycare Mighty Bambinis, has written a blog post for us drawing on her expertise running a daycare as well as her Masters in Education to help us understand what questions we should REALLY be asking on a preschool tour to get a feel for whether a preschool is going to be a good fit for your family. That post will be out next week, but if you want to get a headstart (or you have tours coming up this week!) head on over to yourparentingmojo.com/preschool to download a really cool printable list of questions to take on a preschool tour with space for you to jot down your answers. That printable is available right now, and if you’ve subscribed to the show through my website then you actually received it in the same email I used to let you know that this show is live. If you’re not subscribed through my site then head on over to yourparentingmojo.com/preschool to download the printable to take with you on your tours, because it’s going to let you know the kinds of questions to ask and things to look out for that will help you to judge the real quality of a care setting, which the literature shows is not as easy to judge as you might imagine.

OK, now into the research. I want to lay just a little bit of groundwork with research on the effects of daycare in infancy, even though that isn’t our focus. A lot of the studies looking at daycare and preschool takes advantage of policy changes related to parental leave in European countries, and looks at shift in children’s abilities before and after the change. And as a little methodological side note, these studies are done in a pretty different way from the usual ones we see on the show where a researcher takes 50 children into a lab and asks 25 of them to do one kind of task and the other 25 just play a game and the researchers ask both groups to do a different task and see which children can do it better. For many of these studies the researcher calls up, for example, Statistics Norway and says “could you please send me the data you have on the percentage of mothers that worked the year before and after the maternity leave increase, as well as the test scores for all five-year-old students in the country in those years, and also the final graduation rates and test scores for those children when they left school?” and Statistics Norway says “certainly Madam; we’ll send it to you within a couple of weeks” and the researcher can just sit in their office and run some statistical analysis on the data. So this data can give us some incredibly powerful country-level information that would otherwise be prohibitively expensive to gather by an individual researcher. But we should also acknowledge that this data isn’t able to tell us much about the individual-level processes going on. A child might score poorly or well on a standardized test for a host of reasons not related to the amount of time they spent in daycare or preschool, so while these studies can tell us about how children *on average* respond to being in daycare or preschool, they don’t tell us much about how YOUR CHILD will respond to this.

So one study on infant care compared child outcomes after an increase in mandatory paid maternity leave from 0 to 4 months, and mandatory unpaid maternity leave from 3 to 12 months in Norway in 1977. These children were 29 in 2006 when the study happened, and the study found that 2.7% more of the children completed high school after the reform, going up to 5.2% for those whose mothers have less than 10 years of education. There wasn’t really any high quality childcare available in Norway for under two-year-olds at the time, so the alternative was grandparents or other informal care, so this isn’t really a comparison between the kinds of care that most of my listeners are considering. An American study found that children whose mothers worked during the first year had lower scores on a test of cognitive ability and verbal intelligence, but this was potentially offset by a positive effect when the mother works in the second and subsequent years. The negative first year effect wasn’t impacted by the increased maternal income that came with the mother’s work, although this did appear to play an important role in producing the positive effect in the second and later years, but this study didn’t look at the kind of care the mother was using so we don’t know if it was center-based or informal (which is a pretty important distinction, as informal care is regularly associated with detrimental outcomes for children), and we also don’t know anything whether these differences between the two groups persisted as the children got older.

Another American study aimed to control for factors that might have differed between families using daycare and families not using daycare – so things like the fact that women who return to work earlier may provide a less nurturing or stimulating home environment and be less likely to breast feed, and the type of care used. These researchers found adverse effects of maternal employment on cognitive outcomes for non-Hispanic White children, but not for African American or Hispanic children, that persisted until age 7 or 8, although the effects were not large and were worse among lower-income families. The child’s home environment was an important factor predicting cognitive ability, breastfeeding didn’t seem to impact the results one way or the other, with informal care provided by non-relatives again producing the worst outcomes. One particularly pessimistic study said that looking at young children’s verbal ability isn’t a very good way of assessing the impacts of maternal work because we should actually be looking farther ahead, and if we do that, we see that mothers’ early work is linked with worse performance on reading and math tests at age 5 and 6 – about the same decline in performance as if the mother had 2-3 years less education than she really does. This is one of the few studies that looked at part-time employment and found a reduced but still negative effect for part time work, but the effects of the type of daycare used were highly mixed. It also disaggregated the results by economic status, noting that “children with working parents come from relatively advantaged backgrounds or possess attributes associated with rapid cognitive development,” which is a bit opaque to me but I think what they’re saying is that White middle class parents are “good parents,” and when these parents spend less time with their children because they’re working, the children experience adverse outcomes. Once again, however, what we’re really measuring is the ability of all children to do well on the types of tests that predict academic ability in a system that is really designed for White children to succeed in. So that’s what some of the research on working while the child is very young has found – in general, it seems to be more negative when low quality care is used and the parent is “advantaged,” and may be somewhat offset if the mother continues to work in subsequent years.

But what happens if the mother remains at home for the child’s first and maybe second year, and then returns to work after that? The research on this front is decidedly mixed, so we’re going to spend some time teasing it out. Once again, there is a large body of work demonstrating the “benefits” of high quality care for the population of welfare recipients, largely because the skills that these families develop in their children are not ones that are valued in school so formal daycare environments get these children used to functioning in an environment where you need to sit still and listen to the teacher, which helps the children once they get to school since sitting still and listening to the teacher is a valued skill in that environment. In other words, White middle class parents do just fine at preparing their children to succeed in a school that espouses White middle class values, a finding that is echoed in several other studies as well.

A couple of studies looked at Norway’s 1998 Care-for-Cash reform, which provided cash to families with young children who did not use formal child care facilities and instead took care of their infant or toddler themselves, used grandparent care, or used other informal care. This program apparently reduced the score on a reading test by about 1.24% among mothers with low levels of education. There’s a small increase in the scores driven by increased income from the mothers going back to work, but this is offset by the use of low quality informal child care and encourages the mother to have more children who will also have lower scores. But on the flip-side of that, another study found that older children whose mothers had an infant or toddler who made them eligible for the Cash-for-Care program actually had a better-than-expected 10th grade GPA, possibly because the school day in Norway is short and students get a lot of homework assignments but after-school programs are of low quality, so having the mother available to help could have supported the older child’s educational achievement. But this was just a tentative hypothesis, as the study didn’t seem to fully explore the link between maternal education or family income and the child’s outcomes. It’s possible that White middle class mothers might have provided more effective homework support for children than lower income mothers from other backgrounds.

Now I want to take a little detour here because I’ve mentioned the terms “high quality” and “low quality” a few times now, and you’re probably wondering “well, what IS a high quality preschool?”. It seems as though that should be a relatively easy thing to define, but it turns out that it’s actually not. Some researchers in the U.K. looked at the indicators that the U.K. Schools Inspectorate, which is called OFSTED, uses measure quality – things like staff qualifications, the staff-child ratio and group size, which roll up into a score of Outstanding, Satisfactory, or Inadequate. It turns out that attending preschool that is rated Outstanding is associated with moving up less than one level on just one of the 13 scales that make up the Foundation Stage of primary education at age 5, and children who attend Inadequate preschools do not always have the lowest readiness scores. It seems as though the type of administrative data that is usually used to measure quality is easy to collect and conveniently objective, but the actual experiences of the children in the setting, which is also called “process quality,” can only be measured by actually observing children in the setting – which makes this data very time-consuming and expensive to collect (which is why nobody does it on a large scale). Other studies have found positive but weak relationships between the average qualification level of staff and process quality; specifically for social skills like being cooperative, sociable, and less worried and upset. The same researchers found that helping some of the nursery staff to achieve a qualification leads to a significant improvement in process quality, but studies in the U.S. have found few associations between qualifications and quality at all. The blog post that I’m working on with Evelyn Nichols that will be published next week will help you to ask questions when you go on preschool tours that will help you to get at some of these process quality metrics, and the printable is something you can actually take with you so you remember what questions to ask and have space to jot down some short answers.

I should acknowledge that pretty much all of the research that I’ve found on quality is related to quality in formal daycare centers, rather than related to in-home nannies or nanny shares (which are a pretty common way to care for young children among the middle class in the U.S.), or in informal settings like the grandmother down the street who takes in the neighborhood children for a pretty cheap rate and probably does not have any formal qualifications. Daycare centers and preschools are much easier to inspect and assign numerical scores to, so that’s where the research seems to focus.

OK, so back on to the implications of being in preschool for children. A study by Dr. Christina Felfe in Germany published in 2012 looked at changes in parenting practices after the expansion of parental leave from 3 months in 1979 to 36 months of job protected leave and 24 months of that being paid leave (which probably makes American parents want to cry). In contrast with previous studies conducted in Quebec, which found that the introduction of a childcare subsidy led to more hostile parenting styles and thus to a deterioration of child well-being, this one in Germany found that the quality of maternal care does not deteriorate as a result of sending the child to center-based care. The paper notes that this could be because the kinds of activities that get crowded out in the mother-child interactions are things like running errands and watching TV, and I did want to linger on this point for just a minute. Firstly, I think that running errands actually has the potential to be a very rich interaction for children; my 4.5YO daughter Carys loves to come grocery shopping with me and we spend quite a bit of time talking about the things we’re buying and now she’s receiving pocket money I imagine the cost of items is going to become more of a discussion point. She helps me to unpack the bags when we get home, which Dr. Roberta Golinkoff cites as a perfect example of an activity that supports the development of skills related to cooperation. It also reminded me of things I’ve read in the homeschooling literature discussing how parents whose children are in school tend to run errands while their children are at school, but it turns out that running errands is a lot of what life is about. As a result, many children get to age 16 or 18 never having been in a bank or a post office or having any idea how to interact with the staff of those institutions. There’s a real tendency in modern parenting to get these kinds of errands out of the way so you can do the “fun stuff” with your children, but when you’re a stay-at-home parent the children are around all the time so these errands become a natural part of their lives and they see what it means to be an adult rather than being apart from adults in school and learning how to be an adult there. And the other part of this that caught my attention was the observation that low-quality solo time in front of the TV is something the child is less likely to spend time doing if they attend preschool, which reminded me of an article the New York Times ran just a couple of days ago discussing the pressures of modern parenting. It talked about how the American Academy of Pediatrics is contributing to this trend by saying that if parents do allow their children to watch TV, the parents should sit with the child and discuss what they’re seeing, so it seems as though there’s some tension here between activities we are pretty sure are good for children, and whether we really need to do them *all the time* to be adequate parents. Another reason that maternal care quality can improve when the child is in daycare is if the mother uses that time to work (which I have to say, I was surprised to see that they don’t always do in European countries) and thus have a higher family income. This was a conclusion of the German study, although earlier in the paper the authors had said that the mother’s wage didn’t result in a significant increase in the net household monthly income, possibly due to the cost of childcare and commuting.

I have to say, though, that I was pretty disappointed to find another paper by Dr. Felfe published in 2015 which appeared to reach exactly the opposite conclusions from the 2012 study. I quote: “Subsidized full-day care has negative effects on children’s socio-emotional development: full-day separation from the primary caregiver – who is most likely the mother – entails problems for children’s social maturity and emotional stability.” Rather annoyingly, the 2015 paper doesn’t even reference the 2012 paper, never mind attempt to explain the discrepancies between them. The 2015 paper did note that daycare workers may be better trained at stimulating children’s verbal, analytical, and motor skills, but the mother may be better at promoting socio-emotional development because of the value of the child’s attachment to the parent (you can look back to the relatively recent episode we did on attachment if you need a primer on what that is and why it’s important). Surprisingly, though, it was actually children from lower socio-economic backgrounds that experienced the greatest losses, and the researchers didn’t explain this counter-intuitive finding. I would have thought that if mothers were critical to supporting the development of social and emotional learning and middle class mothers were more adept at promoting this learning (which the paper says they are), then middle class children attending preschool should experience more of a drop-off in these skills than children from lower socio-economic backgrounds, but the opposite result was actually found. Unfortunately the data in both of these studies is related to children aged 0-3, and the researchers were not able to disaggregate it. I would expect to see a pretty profound difference in putting an infant in daycare than putting a three-year-old in preschool, but we have no way to understand this discrepancy using this data. Other researchers looking at the 1975 expansion of universal daycare in Norway have found that “the benefits of providing subsidized child care to middle and upper-class children are unlikely to exceed the costs,” probably because the primary driver of benefits to lower-class children was an increased likelihood to graduate from high school, and children from middle and upper classes are already pretty likely to graduate from high school. The researchers seem to be arguing against the case for universal daycare for children from middle and upper classes, but while they note that exposure to low income parents has little impact on the outcomes of children of high income parents, they don’t comment on the reverse case – whether some of the benefit of being in preschool for low-income children is because they gain exposure to children of high-income parents, who are modeling the types of behavior seen as desirable in school.

Dr. Felfe has also looked at children’s cognitive development, and finds that reading test scores at age 15 increased by about 0.15 standard deviations among children who were in preschool at age 3, but no evidence of an advantage on math performance was found. In addition, children who attended preschool at age 3 were about 2.5% less likely to be held back a grade in primary school, so there’s a benefit there although it’s a pretty small one. As usual, these effects are largely driven by children from “disadvantaged” families, and, interestingly, by girls. Another researcher, Dr. Margherita Fort, actually found the opposite effect on girls, so – a disadvantage to being in daycare between the ages of 0 and 2 – among affluent families in Bologna, Italy. She hypothesized that this is driven by three factors – firstly, if the care environment has a high child:teacher ratio then the child is deprived of the 1:1 interaction that is valuable to their cognitive development. Secondly, the quality of these interactions may be higher at home, and thirdly, girls may be better positioned to make good use of these interactions at an earlier age since girls’ cognitive development seems to lead that of boys by a couple of months at young ages. Dr. Fort found that this detrimental cognitive impact was actually quite large: a 1.6% drop in IQ scores per additional month a girl spent in daycare between the ages of 0 and 2, although when both girls and boys were considered together the effect dropped to a 1.1% decline.

An often-cited study done in Quebec found negative impacts on the cognitive development at age 5 among children who attended preschool at a young age (which was also present at age 4, although not at a statistically significant level), and a follow-up on that study found that the younger the child was when they entered daycare in Quebec, the greater the negative outcomes. Yet what is often not mentioned in the citations of these studies is that the government of Quebec had decided to rapidly expand childcare to all children in the province, and did it so quickly that they actually couldn’t find enough qualified teachers so they accepted daycare workers with no specific training in early childhood education. In addition, around half of the centers didn’t respect the maximum ratio of number of children per qualified educator, and other studies found that the average quality in Quebec’s subsidized daycare network is at best satisfactory and in many cases low or not acceptable, particularly for children in lower-income families. It is thus not surprising that a negative impact on children’s cognitive development was found in this study, but we should also realize that unless you live in an area where the government is rapidly expanding daycare availability or there are other indicators that the center you’re considering is low quality, then these results aren’t really applicable to your situation.

Other authors have looked at German data on children whose birthdays occur around December and January. Because of a quirk in the way German preschool works, children with December birthdays are eligible to start preschool earlier and end up receiving about 400 extra hours in daycare than children born in January. The researchers found that these extra hours of daycare essentially had no benefit at all either on their cognitive skills, on what academic track the children ended up, or on non-cognitive skills related to the children’s strengths and differences and what’s called Big Five personality traits, which are important as they strongly predict later educational outcomes, job outcomes, and risky behavior.

Dr. Felfe and another colleague have also looked at the other end of what happens when a child starts attending daycare, which is how what happens at home changes. They used a previously collected set of data that asked mothers to complete diary entries of the amount of time on a random weekday and a random weekend day on each of three kinds of activities: educational activities like studying, doing homework, and reading or being read to, structured leisure activities like arts, crafts, music, and theater, and playing sports, and unstructured activities like watching TV, listening to music, and unspecified leisure activities like time reported “doing nothing” and “wasting time.” In addition, mothers were asked about their employment, and children were tested on scales of cognitive and behavioral tests. They found that working mothers spent about six few hours per week with their children engaged in unstructured activities, activities that require the least amount of verbal exchange and direct engagement from both mothers and children, but there was no significant effect of maternal employment on time children spent with mothers in educational and structured activities that require direct verbal exchanges and involvement – activities which (the researchers say) are the types of activities that most positively correlate with child development. The researchers say that “the reduction in unstructured time resulting from working full-time versus not working outside the home leads to an improvement in children’s cognitive outcomes of 0.03 to 0.04 standard deviations, and for children younger than 6 years these effects are even larger – between 0.08 and 0.09 standard deviations. These estimates amount one quarter of the correlation between the preschooler’s cognitive outcomes and the mother’s education, which is a widely acknowledged determinant of child outcomes.” I found a couple of big problems with this study, though. Firstly, correlation does not necessarily imply causation – we can’t know for sure that spending less time on unstructured activities is what caused the improved cognitive outcomes for these children. And secondly, I would worry that working mothers would hear the results of this research and say “well I’d better spend every waking second making sure I’m doing educational or structured activities with my child or their cognitive development is down the toilet.” I was interested to see that these researchers did not account for time spent on a whole host of activities that could be done with children that do benefit their development – things like going grocery shopping (like we already mentioned), cooking dinner together, matching the socks while doing laundry together, playing with Legos or blocks dress-up clothes, going for a nature walk, roughhousing, having unstructured outdoor play time, and – I would argue, although I haven’t done a full episode’s worth of research to be able to back this up yet – spending some time just relaxing together and enjoying each other’s company without feeling pressured to “do something.” Just because some activity is associated with improved cognitive outcomes doesn’t necessarily mean that the more you do of that thing the better the cognitive outcomes for your child. So I would advise spending some time together on more structured activities, but also not neglecting the value of time spent together on everyday tasks and even time spent “doing nothing.” A Dutch study also found that children of working mothers experienced a cognitive benefit, although they could not explain their finding using any of the data they had on hand, which included the time mothers and children spent on various activities, so these results contradicted Dr. Felfe’s findings. They theorized that the mother’s income could provide better nutrition or access to goods or services that are beneficial to the child’s cognitive development, or possibly that working mothers exchange information and experience regarding time management, child care centers, and child-raising activities with their colleagues, or that the mothers in the question enjoy both working and being a parent.

Before we leave this mess of literature behind and reach some conclusions, I did want to point out one final study which used data from two international surveys of over 100,000 men and women across 29 countries, which found that daughters who were raised by working mothers were more likely to work themselves as adults and if they did work, were more likely to supervise others, work more hours, and earn higher incomes. These daughters also spent less time on household tasks, while sons spent more time caring for family members relative to sons raised by mothers who were not employed. The researchers found that gender attitudes partly accounted for the association between maternal employment and adult daughters’ employment outcomes, as well as the social learning that takes place as the daughters look back to their own mothers’ ability to manage employment and caregiving and realize they can do this themselves as well.

So, what are we to make of all this? Firstly, I would say that if you can afford to stay home for your child’s first year, the research indicates your attachment relationship with your child will likely benefit. For mothers in Europe who get this much time off PAID, this is likely a no-brainer; for Americans who are entitled to a few weeks of maternity leave if any at all, this may be disturbing to hear. Now I’m not saying that if you put your child in daycare at six weeks of age because you have no choice but to go back to work that your child won’t be able to form an attachment relationship with you, because that’s simply not the case. But there are a lot of benefits associated with being in close contact with the primary caregiver in that first year that the child may miss out on by being in daycare in a setting where there are more than a couple of children assigned to each caregiver, and thus the opportunity for one-on-one interaction is reduced.

Once the child gets to somewhere between one and two, the considerations shift a bit, and it really isn’t totally clear whether the child will benefit from being in preschool or not. To some extent I think it depends on the child – a highly social child with an introverted mother seems likely to benefit from an external setting. An introverted child who struggles with transitions may need more time before they are ready to be away from the parent on a regular basis, if this is an option. Parents might be tempted to put their child into care part-time, although I’ve seen anecdotal parental experience saying that children struggle with an on-off-on-off-on schedule, or even a four days off/3 days on schedule since with the first they can never get into a real routine and with the latter the routine gets upset just as they’re getting into the swing of it. If you do want to try part-time work and part-time care, it would probably be better to do five mornings rather than two or three full days.

And in terms of evaluating the quality of a daycare, you definitely can look for child:teacher ratios, teacher qualifications and the like, but just be aware that these things ALONE cannot tell you whether a setting is high quality or not. The only real way to assess quality is to visit the setting and look for the kinds of indicators that indicate quality – the kind that researchers know to look for but never seem to have the time or money to collect. But just as a reminder, if you go to yourparentingmojo.com/preschool, you can download that checklist that Evelyn Nichols of Mighty Bambinis and I put together for questions you can ask while you’re on a preschool tour as well as things to watch out for and questions to ask yourself about your experience on the tour that will help you to assess the quality of the setting. It seems pretty likely that the best child outcomes are associated with high quality settings, so this checklist is really on the money if you want to be as sure as you can be that your child’s own experience is going to be one that makes a positive contribution to their cognitive and social development.

And please, above all else, if you must or even if you just WANT to go back to work, don’t beat yourself up about it. If the money enables your family a higher standard of living than you would otherwise be able to have, that’s a good thing for your child. If you do go back to work, don’t feel as though every minute you spend with your child has to be geared toward their cognitive and socio-emotional benefits, because just engaging in normal daily activities with your child has a benefit that is often overlooked by the researchers who study this topic. And, finally, if overcoming gender boundaries is important to you then it’s possible that working will model behavior for both your daughters and sons that will help with this in the future.

I hope this helps you to understand this topic a bit better, and also to relax about it a bit more. And don’t forget to head to yourparentingmojo.com/preschool to download that checklist, unless you’re already a subscriber to the show in which case you received it with the notification about this episode.

Thanks again for listening – talk again soon.

References

Bettinger, E., Haegeland, T., & Rege, M. (2013). Home with Mom: The effects of stay-at-home parents on children’s long-run educational outcomes. CESifo Working Paper No. 4274. Center for Economic Studies and IFO Institute (CESifo), Munich. Retrieved from http://hdl.handle.net/10419/77681

Blanden, J., Hansen, K., & McNally, S. (2017). Quality in early years settings and children’s school achievement. CEP Discussion Paper #1468. Centre for Economic Performance.

Blau, F.D., & Grossberg, A.J. (1990). Maternal labor supply and children’s cognitive development. Working Paper No. 3536. NBER Working Paper Series, National Bureau of Economic Research. Retrieved from https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/6708064.pdf

Carneiro, P., Loken, K.V., & Salvanes, K.G. (2010, December). A flying start? Long term consequences of maternal investments in children during their first year of life. Discussion paper series // Forschungsinstitut zur Zukunft der Arbeit, No. 5362. Retrieved from https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/b580/c5b64c2ac7f7706963516265353f4c5fc164.pdf

Chan, M.K., & Liu, K. (2015). Life cycle and intergenerational effects of child care reforms. Discussion Paper No. 9377. Institute for the Study of Labor, Bonn, Germany (Forschungsinstitut zur Zukunft der Arbeit). Retrieved from http://ftp.iza.org/dp9377.pdf

Felfe, C., & Lalive, R. (2012). Early child care and child development: For whom it works and why. Discussion Paper No. 7100. Institute for the Study of Labor, Bonn, Germany (Forschungsinstitut zur Zukunft der Arbeit). Retrieved from http://hdl.handle.net/10419/69379

Felfe, C., Nollenberger, N., & Rodriguez-Planas, N. (2014). Can’t buy mommy’s love? Universal childcare and children’s long-term cognitive development. Journal of Population Economics 28(2), 393-422.

Felfe, C., Zierow, L., & Maximillians, L. (2015). From dawn till dusk: Implications of full day care for children’s development. Retrieved from http://conference.iza.org/conference_files/SUMS_2015/zierow_l21761.pdf

Fort, M., Ichino, A., & Zanella, G. (2016). Cognitive and non-cognitive costs of daycare 0-2 for girls. IZA Discussion Paper No. 9756, Institute for the Study of Labor (IZA), Bonn, Germany. Retrieved from http://hdl.handle.net/10419/141515

Haeck, C., Lefebvre, P., & Merrigan, P. (2013). Canadian evidence on ten years of universal preschool policies: The good and the bad. Working Paper 13-34. Centre Interuniversitaire sur le Risque, Les Politiques Economiques et l’Emploi. Retrieved from http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.687.2067&rep=rep1&type=pdf

Havnes, T., & Mogstad, M. (2015). Is universal child care leveling the playing field? Journal of Public Economics 127, 100-114.

Hsin, A., & Felfe, C. (2014). Children’s time with parents, and child development. Demography 51, 1867-1894.

Kottelenberg, M.J., & Leherer, S.F. (2013). Do the perils of universal child care depend on the child’s age? CESifo Economic Studies 60(2), 338-365. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Steven_Lehrer/publication/275380692_Do_the_Perils_of_Universal_Childcare_Depend_on_the_Child%27s_Age/links/586d9c8108ae8fce491b5e94/Do-the-Perils-of-Universal-Childcare-Depend-on-the-Childs-Age.pdf

Kuehnle, D., & Oberfichtner, M. (2017). Does early child care attendance influence children’s cognitive and non-cognitive skill development? Working Paper No. 100. Institute for the Study of Labor, Bonn, Germany (Forschungsinstitut zur Zukunft der Arbeit). Retrieved from http://hdl.handle.net/10419/156403

Kunn-Nelen, A., de Grip, A., & Fouarge, D. (2014). The relation between maternal work hours and the cognitive development of young school-aged children. De Economist 163, 203-232.

Miller, C.C. (2018, December 25). The relentlessness of modern parenting. The New York Times. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2018/12/25/upshot/the-relentlessness-of-modern-parenting.html

McGinn, K.L., Castro, M.R., & Lingo, E.L. (2018). Learning from Mum: Cross-national evidence linking maternal employment and adult children’s outcomes. Work, Employment & Society (Online first). DOI 10.1177/0950017018760167

Ruhm, C.J. (2004). Parental employment and child cognitive development. The Journal of Human Resources 39(1), 155-192.

Waldfogel, J., Han, W-J., & Brooks-Gunn, J. (2002). The effects of early maternal employment on child cognitive development. Demography 39(2), 369-392.

Also published on Medium.

Hi! I just listened to this and wish I had heard it before my son began nursery over a year ago!

I especially enjoyed how you emphasise that just doing everyday activities with your children is beneficial to them – it can be challenging when we feel we have to be constantly playing with them or coming up with things to do in order to support their development.

One thing that might have been useful to mention is that for some parents, the risks associated with daycare/preschool are worth taking simply because the mental health of the parent is otherwise at stake – many parents cannot tolerate being the sole caregiver to a child or children for 8-12 hours a day and the effects that this can have on the parent-child relationship can be devastating. Even if one parent is ‘at home’, daycare or preschool might still be beneficial.

You’re absolutely right, Molly – I’d probably even put myself in this category, especially with very young children. Perhaps some kind of informal care could be a bridge between formal programs and being home alone with the child all day every day? The nuclear family is certainly very odd from the perspective of human history; in the past (and in many cultures today) we would have had so many other family members around who could share the burden…

Yessss- I was losing my mind being home with twins for three years! I finally found a subsidized program, because we couldn’t afford anything- and the downside is that they must attend a minimum of 32.5 hours per week (mandatory). I would prefer a part time situation, but it sadly would be out of our budget…

SHARE THE LIST OF QUESTIONS PLZ.

Hi Megha – you can download the questions by entering your name and email address in the box on this page. Do let me know if you have problems with it.