The Anxious Generation Review: What the Research Actually Shows

Key Takeaways

- The teen mental health crisis may be less severe than headlines (and The Anxious Generation) suggest. Much of the scary data shows better screening and diagnosis rather than new cases caused by social media. The changes are not as widespread as the book makes them appear. They are at least partly explained by changes in how we diagnose and label mental health conditions.

- Social media’s impact on youth mental health is surprisingly small. Research shows social media explains less than 1% of teen wellbeing. It’s about the same as whether or not the teen eats potatoes. While statistically significant in large studies, this effect on an individual child is tiny compared to factors like family relationships and academic pressure.

- The most vulnerable teens aren’t the ones that The Anxious Generation focuses on. While The Anxious Generation prioritizes (assumed: White middle class) teenage girls, suicide rates and signs of youth depression remain much higher for boys and men. LGBTQ+ teens and some Native American communities face the biggest mental health risks. These problems often have nothing to do with social media. Helping these groups would make a much bigger difference than just keeping white middle-class girls off social media.

- Family relationships, friendships, and school stress matter way more than screen time for youth mental health. When teens go to emergency rooms for self-harm, 64% say family problems are their biggest worry. School stress, friend drama, money troubles, and school problems matter way more than technology for Gen Z mental health.

- Phone bans address symptoms while ignoring underlying needs. Kids use phones because they meet needs for independence and connection. School often doesn’t provide these. Banning devices without addressing why kids want them is like taking away a crutch without healing the broken leg.

- Control-based parenting approaches often backfire with technology. Just like the failed “Just Say No” drug campaigns, strict phone rules can damage trust and push teens away when they need guidance most. Kids who fear punishment can’t come to parents when they encounter problems online.

- Building connection works better than imposing restrictions for mental health for teenagers. The best protection for teen mental health isn’t limiting screen time. It’s creating relationships where kids feel seen and supported. Working together on technology rules works better than forcing blanket rules.

Note: This blog post is based on a four-part podcast series, where we took a deep dive into Jonathan Haidt’s The Anxious Generation.

Find a collection of resources related to The Anxious Generation on this page.

If you’re a parent, you might worry when you see your child on their phone all the time. You might feel upset when they pick their screen over talking at dinner. Or maybe you’re scared that their phone is somehow changing their brain in bad ways. You might wonder: Is this normal teen stuff, or is something different happening to kids today?

Jonathan Haidt’s bestselling book The Anxious Generation seems to confirm our worst fears. The book shows scary charts of teen depression and anxiety going way up. Haidt says this is clear proof that smartphones and social media are causing a mental health crisis in our kids like never before.

The book’s central claim is compelling in its simplicity. Between 2010 and 2015, Haidt says kids stopped having a “play-based childhood” and started having a “phone-based childhood.” He thinks this change rewired kids’ growing brains and caused more suffering than any kids before them had experienced.

For worried parents, The Anxious Generation offers both validation and a clear villain. Those endless battles over screen time? The way your once-chatty teen now grunts responses while staring at their phone? The anxiety you see in their eyes that wasn’t there a few years ago? According to Haidt, these changes are not just connected to but caused by their phone.

But before we panic and ban our kids’ phones (at school or at home), we should look more closely at what the research actually shows. Our parental worries about technology might feel urgent. But the scientific picture is far more complex than Haidt’s compelling narrative suggests.

What if the crisis isn’t as big as those graphs make it look? What if the jump in reported mental health problems just shows changes in how we find and track these conditions? Not new cases caused by social media? What if focusing only on screens makes us miss the real things causing our teens’ problems?

Parents everywhere are asking: Is social media really destroying our kids’ mental health? The answer isn’t as simple as The Anxious Generation makes us believe.

What Is The Anxious Generation About?

Haidt’s book presents a clear narrative. Between 2010 and 2015, we saw the decline of what he calls the “play-based childhood” and the rise of the “phone-based childhood.” This shift, he argues, is responsible for dramatic changes in Gen Z mental health. The evidence seems compelling at first glance. The seemingly endless graphs show rising rates of teen depression, anxiety in teenagers, and self-harm episodes.

He also points to the front-facing camera on the iPhone 4 as a key driver of the shift in 2010, as well as Instagram reaching mass usage in 2012. This means that Haidt sometimes points to 2010 as the beginning of a key shift, and sometimes to 2012. His collaborator Dr. Jean Twenge was raising the alarm as early as 2007, when the first iPhone came out. This raises the question of whether the data have been picked to confirm a theory, rather than the theory coming from the data.

And when we dig deeper into this data, some troubling patterns emerge. Many of these dramatic-looking increases might not be what they seem.

The Hockey Stick Graphs: Crisis or Perception?

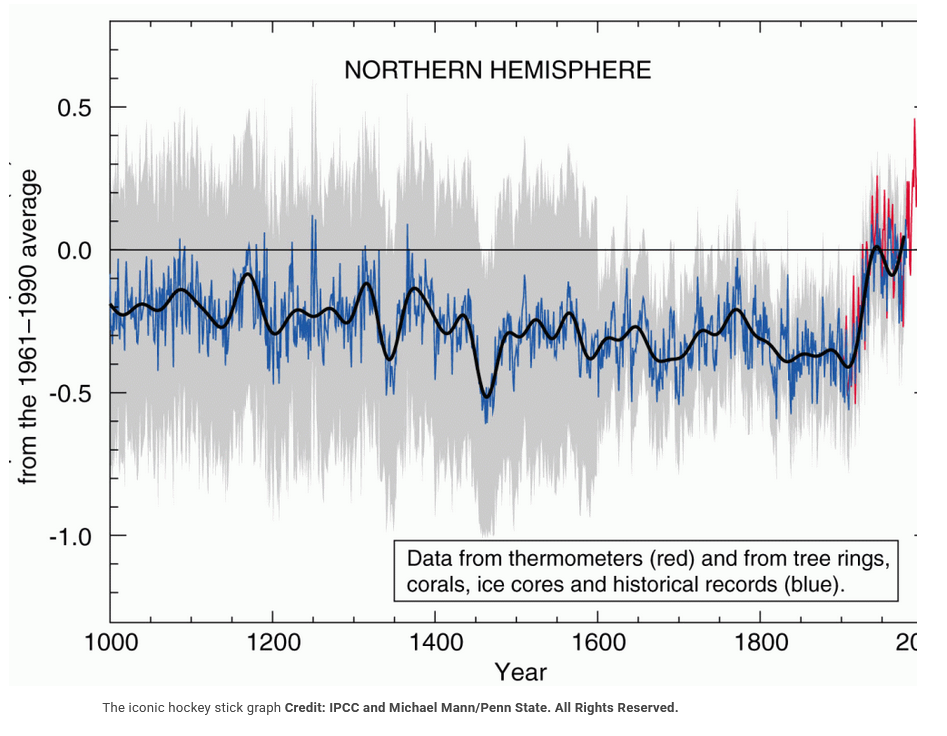

The Anxious Generation review of data includes dozens of alarming statistics, many on graphs that are shaped similarly to the ‘hockey stick’ graph responsible for convincing many people that climate change is real:

In the first of my detailed podcast episodes on The Anxious Generation, I focused heavily on suicide data. I figured it would be easier to understand than the many different measures of whether someone is experiencing mental health challenges.

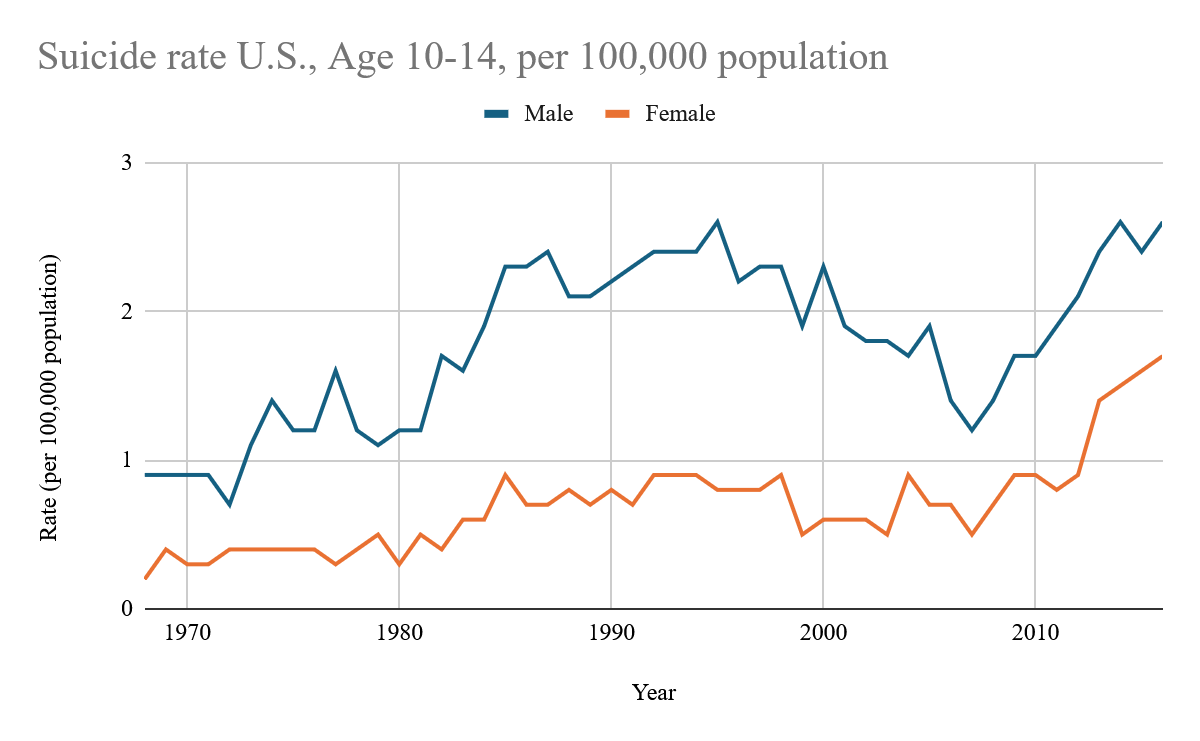

Here’s the data I found on the suicide rate for girls age 10-14:

Data Source: https://wonder.cdc.gov/mortsql.html (Note: Haidt’s graph continues with data from 2017-2020, which I couldn’t independently verify from CDC sources)

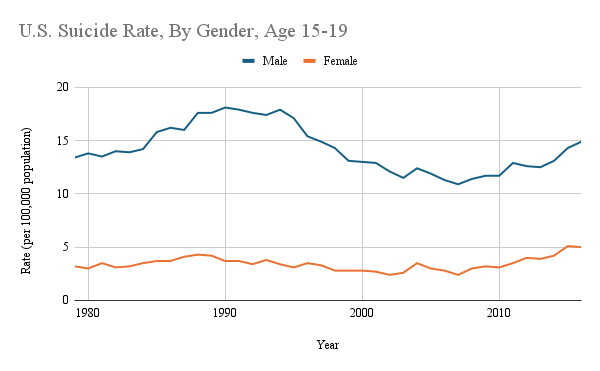

According to Haidt’s data, the suicide rate for girls is up 167% from 2010 to 2020. Haidt also says that the rate for girls age 15-19 doubled from 2010-2020, which may be true, but 2009 was a historic low point and overall the rate isn’t a lot higher than it was in the late 1980s:

Data source: https://wonder.cdc.gov/mortsql.html

But the Pew Research Center found that older teens are much more likely to be online ‘constantly,’ with half of 15-17 year olds saying they were online ‘constantly’ in 2024, compared to 38% of those aged 13-14 (and we can assume that kids younger than 13 are spending less time than this online). So if being online is driving girls to suicide, why aren’t the girls spending most time on social media committing suicide at higher rates?

What this means for you: Those scary numbers you see in The Anxious Generation aren’t happening everywhere like the book makes it seem. The author picks one number from one place and another number from somewhere else to make his point. Some teens really are struggling, but the problem is not universal across all teens.

Here are some other explanations I discovered when we examined the data more carefully:

Changes in mental health screening and diagnosis affect reported rates

Between 2009 and 2015, we made big changes in the U.S. in how we identify and track youth mental health issues:

- 2009: The US Preventive Task Force recommended depression screening for teens aged 12-18.

- 2011: The Affordable Care Act required coverage for evidence-based mental health services.

- 2012: Health insurance plans were required to cover annual depression screenings for girls aged 12 and older.

- 2015: Mandatory new diagnostic codes made it easier to identify intentional self-harm in hospital records.

- 2016: CDC guidance changes ICD-10 coding guidelines to include symptoms and signs codes (R40-R46) as an Exclusion 2 note for mental disorder codes (F01-F99) implies that SI should be coded as a secondary disorder when other mental health disorders are primary.

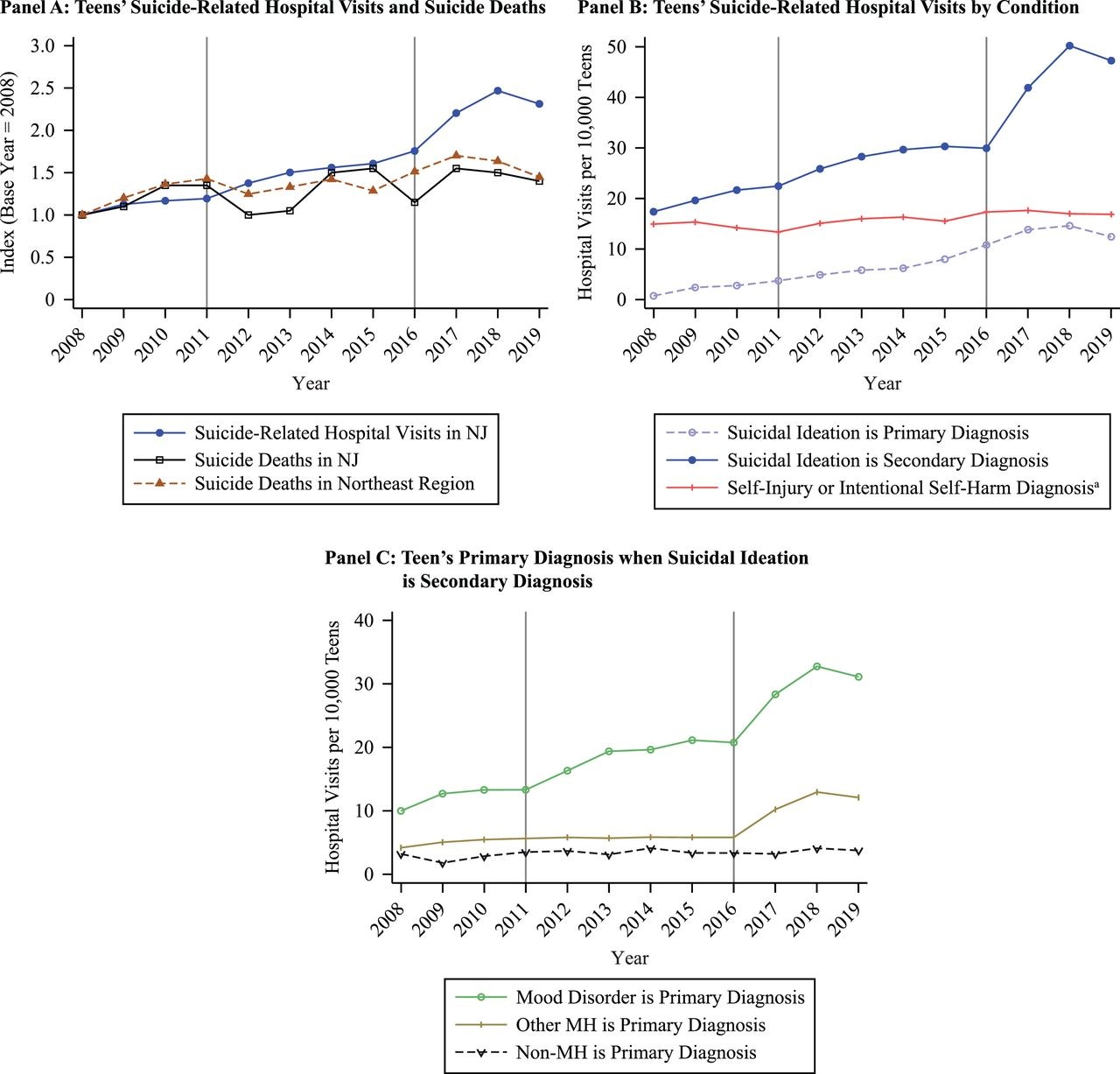

Figure source: https://jhr.uwpress.org/content/59/S/S14

Author’s notes: These figures plot trends in suicide-related hospital visits, suicide deaths, and suicidal ideation hospital visits in New Jersey. The vertical lines at 2011 and 2016 help to visualize the changes related to the implementation of the Women’s Preventive Services Guidelines in 2012, as well the difference between 2015 and 2016 (implementation of ICD-10) and between 2016 and 2017 (implementation of the “include SI” [Jen’s note: as a secondary diagnosis when other mental health conditions are present] guidance).

The authors conclude: “These results suggest that underlying suicide-related behaviors among children, while alarmingly high, may not have risen as sharply as reported rates suggest.”

What this means for you: The dramatic increases in reported teen depression might say more about our healthcare system getting better at identifying, treating, and classifying problems. They aren’t about phones making things worse. Before panicking about your teen’s screen time, consider other changes in their life. These may be academic pressure, family stress, or friendship issues, might be more important to address.

The scale of the increases look worse than they really are

Haidt also visually manipulates data on the graphs in the book. When he describes “dramatic increases” in school alienation worldwide, he’s actually talking about changes of about 0.2 points on a 4-point scale (Figure 1.12, Alienation in School, Worldwide) but the graph is zoomed in to the scale between 1.6 and 2.2 so those 0.2 points look like a huge increase.

Figure 1.8 shows Excellent or Very Good Mental Health, Canadian Women; those aged 15-30 visually appear to have reported near-perfect mental health in 2003 and are now close to the baseline. But the baseline is 50%, and the top of the scale is at 80%, so the decline appears far more dramatic than it really is.

In a collaborative Google doc that Haidt maintains, Haidt observes two ‘big’ jumps in suicides of 10-14-year-old females in the U.S., from 66 to 88 in 2009, and from 85 to 141 in 2013. He says that the rate for the last five years of data is nearly triple the rate for the first five years. Dr. Chris Ferguson’s counter-argument in the document is that the raw increase in the number of suicides among 45-49-year-old men is 1000 deaths, which is a 900% increase, among comparably-sized populations of about 10 million each.

I want to be clear that I believe that any suicide death is one too many for the families who are left behind. I can’t even imagine the pain and suffering of each of the families who have lost a child in this way, and I’m so sorry they have to experience that. But if you’re looking at raw numbers rather than an increase in rates, you’d do a lot more to prevent deaths by focusing on older men than on teenage girls. Ferguson would fail a senior student research project for trying to make the inferential leaps that Haidt is trying to reach.

The language we use matters. When we talk about a “mental health emergency” or “surge of suffering”, it shapes how we think about solutions. If we believe there’s a tsunami, we reach for emergency measures like blanket phone bans. If we recognize it’s a modest tide, we might consider more thoughtful responses.

The International Data Doesn’t Add Up

Haidt often points to similar trends across multiple countries as evidence for his theory. But when you look closely at the data from the US, UK, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand, the patterns aren’t as consistent as they first appear.

Haidt says that “we see similar trends in the other major Anglosphere nations, including Ireland, New Zealand, and Australia” (p.40-41). Again, while you can see an overall increase from 2009 to 2015 in New Zealand, the suicide rates for girls and young women are within historical averages, and have declined for boys and young men.

Data Source: https://www.health.govt.nz/publications/suicide-facts-data-tables-1996-2015

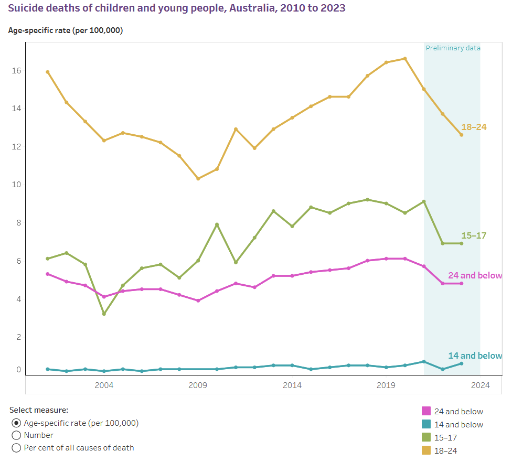

The Australian Institute of Health and Welfare did the hard work of the graphing for me (although I couldn’t find data by gender), and yes, there was a substantial increase in suicides among 15-17 year-olds from around 2010 to 2018, and among 18-24 year olds from around 2009-2020. But the preliminary data shows that the rate has dropped pretty sharply for both groups since 2022, and I don’t think social media has been banned in Australia.

Data Source: https://www.aihw.gov.au/suicide-self-harm-monitoring/population-groups/young-people/suicide-self-harm-young-people

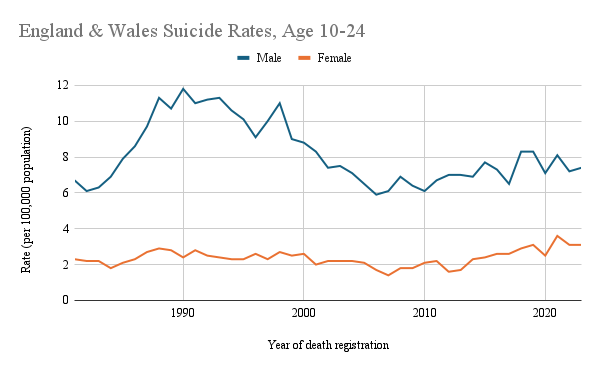

In the U.K., the suicide rate for girls has doubled from 1.4 per 100,000 in 2007 to 3.1 per 100,000 in 2023. But, the rate for boys is a third less than it was at its peak in 1990.

Haidt’s graphs describing mental health crisis symptoms do seem dramatic when the graphs are shown one right after another. When he shows suicide rates for young teens in the U.S., self-harm for U.K. teens, and mental health hospital visits for Australian teens, The Anxious Generation gives the impression that the changes are happening consistently across all the different types of data, across the entire Anglosphere. But this isn’t always the case.

What this means for you: If smartphones were really the main cause of teen mental health problems, we’d see the same patterns in all countries where lots of kids use phones. Since we don’t, it means the real causes are more complicated. This means the solutions need to fit your specific child’s situation.

Only Looking at Gender Camouflages Other Trends

Haidt fails to analyze risk factors other than gender in The Anxious Generation. Among Australian First Nations people aged 0–24, suicide rates were 3.1 times as high compared to non-Indigenous Australians.

I have yet to find suicide data that breaks out transgender youth statistics, but in 2021, more than a quarter (26.3%) of high school students identifying as lesbian, gay, or bisexual reported attempting suicide in the prior 12 months. This was five times higher than the prevalence among heterosexual students (5.2%).

The photo of the slim, blonde, straight, and White-presenting girl looking at her phone on the front of The Anxious Generation isn’t really representative of the actual suicide risk that teens face.

Depression Doesn’t Always Lead to Self-Harm

Studies of people who have considered suicide reveal that different communities experience distress very differently:

- Latinx Americans are more likely to see suicide as escape from poverty, discrimination, and social problems rather than internal mental health issues

- Asian Americans showed higher suicide risk related to interpersonal problems and academic pressure

- LGBTQ+ people aged 18-44 had lifetime suicide attempt rates of 38-44%, often driven by rejection and discrimination

School problems are more than twice as likely to contribute to suicide for Asian and Pacific Islander-Americans compared to white teens. This might be because many Asian-Americans and their parents put a lot of pressure on them to do well in school. But this pressure isn’t only an Asian-American problem. A study of Latina teens who had attempted suicide included one girl named Lola who said:

“I guess I started thinking about, like, my life, like about school. I’m not doing so good. I’m like, “What am I doing with my future?” And I guess it made me kind of sad. [My mom] screams at me. She’s like, “Why don’t you do better? Why don’t you try?” I do try.”

Lola’s mom said:

“I don’t remember these issues growing up. You just did what you had to do, and that was pretty much the end of it. You just do it. You don’t get a gold star.”

Sofia described frequent arguments with her mother about chores. When Sofia did her chores, she believed her mother didn’t notice.

Sofia’s mom told her during a fight: “I don’t care what you do no more. I don’t care!”

Sofia thought her participation in the family was inconsequential, and concluded: “So you don’t care if I die,” and then she took pills.

Her mother interpreted Sofia’s behavior in terms of resistance: “She just doesn’t want to listen. I hope it’s a phase, I just don’t think it’s a phase. I wanna know what it is with her. Because what happens is her anger comes to, ‘I don’t have to do this’. That attitude, it’s like, it’s disrespectful. I’m not your child. I’m your mother.”

A Scottish meta-analysis of ethnographic studies found that teens who self-harmed were often deeply frustrated by adult efforts to link their behavior to social media. Many felt frustrated by attempts to blame social media for their behavior. They saw the narrative that social media was driving their self-harm as wrong and unhelpful. In fact, trying to pin their struggles to one cause often increased their sense of shame and isolation.

These young people talked about self-harm in complicated ways. They said it helped them cope, process big feelings, or they couldn’t explain why they did it at all. If we try to make their pain sound simple, we might miss what they really need for help.

This matters because Haidt thinks that measuring depression and suicide rates shows us what’s wrong with teens. But if different communities understand and feel distress in different ways, we might be missing huge pieces of what’s really going on.

Most research on social media focuses on similar groups of college students. So we might not fully understand how screen time, mental health problems, and suicide connect.

So if the crisis isn’t as bad as claimed, what about the other half of Haidt’s argument? Does social media really cause the mental health problems that teens do face?

Does Social Media Actually Cause Teen Depression?

Jonathan Haidt is adamant that social media causes teen depression. In The Anxious Generation, he writes: “Taken as a whole, the dozens of experiments that Jean Twenge, Zach Rausch, and I have collected confirm and extend the patterns found in the correlational studies: Social media use is a cause of anxiety, depression, and other ailments, not just a correlate.”

That’s a bold claim. But when we dig into those “dozens of experiments,” we find research that’s far less convincing than it first appears.

The Problem with Social Media Research

When students know what you’re studying

Let’s start with one of the studies supporting Haidt’s position: Melissa Hunt’s “No More FOMO” experiment. Researchers told 143 psychology students they were studying social media use, then asked some to limit Facebook, Instagram, and Snapchat to 10 minutes per platform per day for three weeks.

Here’s the problem: the students knew exactly what the study was about. They’d heard countless times that social media is bad for mental health. When researchers then asked them to report on their wellbeing, is there any chance they didn’t know the “right” answer?

Here’s the problem: when you tell college students you’re studying whether social media is bad for them, and they’ve heard this message their whole lives, what do you think they’re going to report? Dr. Peter Gray, who has extensively critiqued this research, points out that despite this built-in bias toward finding negative effects, the study still found:

- No significant effect on overall psychological wellbeing

- No effect on anxiety

- No effect on self-esteem

- No effect on autonomy

- No effect on self-acceptance

Even with this built-in bias toward finding problems, the study barely found anything. No effects on anxiety, self-esteem, or overall wellbeing. Just small changes in loneliness and depression, and only for students who were already struggling.

The Instagram “beauty filter” study

Another study Haidt cites (Kleemans et al. 2018) randomly assigned teen girls to view Instagram selfies, some original, some digitally enhanced to look “extra attractive.” The researchers found that viewing the enhanced photos led to lower body satisfaction.

But again, every teenage girl has heard that perfect Instagram images harm body image. When you tell participants you’re studying “facial preferences” and then show them obviously manipulated photos before asking about body satisfaction, you’re practically telegraphing what you want them to say.

The study also had other limitations:

- Participants viewed 10 selfies in a row (not typical Instagram use)

- Only Dutch girls from similar backgrounds participated

- Effects were measured immediately, not over time

- No control for participants’ mood or baseline body satisfaction

When researchers make it obvious to the study participants that they’re studying whether social media is bad for you, it isn’t surprising when they find that social media is bad for you.

What this means for you: The research claiming to prove that social media harms teens is far weaker than headlines suggest. Studies with serious flaws shouldn’t drive major family decisions. Your energy might be better spent on building a strong relationship with your teen rather than battling over their phone.

The “Natural Experiment” Problem

Given the obvious issues with controlled experiments, researchers have turned to “natural experiments”, studying what happens when broadband internet rolls out to different regions at different times. The logic: if social media really harms mental health, we should see clear declines in mental health as internet speed improves.

Haidt cites studies from England, Spain, and Italy. But the results don’t support his thesis as cleanly as he suggests:

Spain: Effects for men only (or men and women?)

Researchers in Spain tried to look at the connection between the timing of negative mental health effects and the rise of Instagram and TikTok.

They did find a link between broadband and depression, but only for men born between 1985 and 1995, not women. Yet the study’s abstract claims effects for “both males and females.” This kind of inconsistency between results and reporting undermines confidence in the findings.

Italy: Mental health impacts likely aren’t only caused by social media

The Italian study mostly covers a period before widespread social media use, yet still found mental health effects. This suggests that mental health impacts aren’t uniquely tied to social media. They could come from other online activities like gambling or pornography.

England: Confusing results

The English study was the most rigorous, tracking 6,000 children across 3,765 neighborhoods as broadband speeds improved. But the results were puzzling:

- Broadband was associated with better exam performance at age 10-11

- But worse performance at age 16

- The largest effect was a 0.6% decrease in how children felt about their appearance

- No statistically significant relationship between the use of social media and girls’ satisfaction with their friends or family relationships

- Spending 5+ hours on social media per day had an effect size comparable to bullying or family conflict found in other research

One challenge with both the English and Spanish studies is that the researchers split their data by factors like gender, age, and urban/rural areas. But they didn’t state up-front that they were planning to do this analysis. This is a red flag in research when you keep slicing data different ways until you find something that looks significant, you might just be finding statistical noise.

Dr. Jean Twenge’s Work: A Clear Finding of Harm

I looked at all of the papers Dr. Twenge lists on her website that are related to screen time, and I can see why she would be alarmed!

She looks at multiple large datasets, often of over 100,000 people that represent the U.S. population. She finds that teens who use a lot of digital media, especially social media, are twice as likely to report low well-being, depressive symptoms, and suicide risk factors compared to light users.

She finds that this pattern happens in the U.K. as well and is especially strong for girls. The relationship isn’t straight. Teens who use social media for up to an hour a day often have slightly higher well-being than teens who don’t use it. But well-being goes down steadily as you go beyond 1-2 hours per day.

Most of Twenge’s findings are correlational. This means she can say that screen time and wellbeing are linked, but can’t prove that one causes the other. She does cite studies that follow people over time. She does cite longitudinal studies suggesting that more social media use can predict later declines in well-being, rather than a decline in well-being preceding social media use.

She proposes that sleep disruption, displacement of in-person interactions and exercise, social comparison, and cyberbullying create the negative effects.

The Potato Problem: When Big Data Misleads

This brings us to one of the most revealing critiques in this entire debate. Dr. Amy Orben, a leading researcher at Cambridge University, looked at teens’ digital technology use and their wellbeing to see if there was a relationship. She found that there was an association: one approximately the same size as the one between teen wellbeing and eating potatoes.

Both correlations were statistically significant in a dataset of over 60,000 people. Both explained similar tiny amounts of variance in teen wellbeing (less than 1%).

We don’t blame potatoes for teen depression. So why do we blame social media?

This illustrates a crucial problem with big datasets. When you have enough participants, you can find statistically significant correlations between almost anything. The question isn’t whether the correlation exists. It’s whether it matters in the real world.

What the Research on the So-Called Harms of Social Media Actually Shows

When we look at the full body of research on social media and teen mental health, here’s what emerges:

The effects are tiny: Even studies that find bad effects usually explain less than 1% of how teens feel. That’s like saying a teen feels sad because they didn’t eat breakfast while ignoring their family problems, money stress, school pressure, and sleep. Dr. Twenge says 1% matters when you’re talking about millions of people. But other things are still way more important.

The effects aren’t consistent: Dr. Orben’s research shows that scientists can get very different results from the same information depending on how they look at it. Some studies (including Dr. Twenge’s) that show social media is bad pick “the most negative possible” way to look at the data.

Within-person effects are even smaller: Studies that track how changes in one person’s social media use affect their own wellbeing over time show even smaller effects than studies comparing different people at one point in time. This is important because when we think about banning social media or screen time, we’re trying to create a change in a specific person which may not happen.

What this means for you: If social media affects your teen’s mood less than 1%, trying to control their phone all the time might not help much. You should address things like your relationship with them, their sleep, their stress, and how supported they feel at home and school.

What Affects Teen Mental Health More Than Social Media

If social media explains less than 1% of teen wellbeing, what explains the other 99%? Research consistently points to several factors:

What affects teen mental health #1: Family relationships

In the UK study of teens who showed up at emergency rooms for self-harm, 64% cited family relationships as their primary problem. Mental health issues – supposedly driven by social media – ranked fifth.

What affects teen mental health #2: Social connections

This isn’t just about having friends, but the quality of those friendships. Strong friendships can be especially protective when teens aren’t getting support from family.

What affects teen mental health #3: Economic security

The stress of poverty affects everything from where families live to whether parents are home or working multiple jobs. Financial instability has massive impacts on teen mental health that dwarf any effects from screen time.

Children’s suicide rates are higher in counties with a higher concentration of poverty than counties with less poverty. Having money is protective for the people who have it, but not having money can be incredibly difficult for those who don’t.

What affects teen mental health #4: Sleep and physical health

Poor sleep is both a cause and effect of mental health struggles. While screens can interfere with sleep, other factors can too. This may include family stress, feeling unsafe in your neighborhood, and early school start times.

What affects teen mental health #5: Academic pressure

In research on communities like Palo Alto, CA and the anonymized ‘Poplar Grove’ in the book Life Under Pressure where suicide rates are many times national averages, kids don’t describe social media as being an important component of their distress.

These case studies are important because the Palo Alto and ‘Poplar Grove’ teens had everything Haidt says should protect them from social media’s harms. They have tiight community bonds, involved parents, shared values. Yet they experienced suicide rates four to five times the national average. These are the statistically significant risk factors for past year suicidal ideation among the six school districts in Santa Clara County (in which Palo Alto sits):

- Drank alcohol, ever in lifetime

- Use illicit drugs (marijuana, ecstasy, cocaine), ever in lifetime

- Used pain medication, ever in lifetime

- Smoked a cigarette, ever in lifetime

- Female gender

- Self-identify as lesbian, gay, or bisexual

- Feeling sad or hopeless almost every day for two weeks or more, past 12-months

- Experienced violent victimization at school, past 12-months

- Experienced psychological bullying at school, past 12-months

- Experienced cyberbullying on internet, past 12-months > The only item related to phones/social media

- Ever skipped school, past 12-months

In addition to these factors, students perceived academic pressure or distress, general life challenges, depression, feeling disconnected and socially isolated, family or cultural pressure, lack of access to mental health care, poor coping skills, sleep deprivation/disorders, and family economic distress as important risk factors for suicide.

What affects teen mental health #6: School environment

Beyond academic pressure, factors like bullying, feeling unsafe, lack of belonging, and unsupportive teachers all contribute to mental health challenges.

We’ve seen recent increases in the percentage of students who were threatened or injured with a weapon at school, and in the percentage of students who were bullied at school. There has also been a jump in the percentage of students who missed school because of safety concerns either at school or on the way to school.

What this means for you: Focus on being a parent your teen feels safe talking to rather than a parent who monitors their every online move. Ask about their friendships. Notice if they seem overwhelmed by school, and pay attention to how your family dynamics might be affecting them. These factors have far more impact than their Instagram usage.

Blanket Phone Bans Won’t Help All Teens

The Anxious Generation glosses over the idea that smartphone and social media bans may not be beneficial for all teens:

- LGBTQ+ youth often use social media as a lifeline when their families and communities don’t accept them.

- Black teens are more likely than white teens to use social media to get information about mental health.

- Native American girls aged 15-19, who have suicide rates five times higher than white girls, might rely on social media to connect with other Native youth in geographically isolated communities or access mental health resources.

When we create blanket policies for young teens based on research conducted predominantly on advantaged young adults at university, we risk harming the very teens who most need support.

Why This Matters for Your Family

You might be thinking: “Studies have limitations, so what? Shouldn’t we err on the side of caution?”

Here’s why the research quality matters: when studies are this flawed, we can’t tell the difference between correlation and causation. And if we can’t tell what’s actually causing the problems our teens face, we might be fighting the wrong battle.

Imagine if doctors treated every fever by putting patients in ice baths, without checking whether the fever was caused by infection, heat exhaustion, or medication side effects. That’s essentially what happens when we assume screens are the problem without solid evidence.

Haidt points to what he says is a clear decline in children’s mental health and the ‘obvious’ smoking gun of screen time as the single cause. But in our incredibly complicated world with so many things affecting us, what’s more likely? That there’s one single issue creating such a big impact and that screen time is it? Or is it more likely that it’s a complex interplay of issues, of which screen time makes up a fairly small part? Based on the evidence we’ve reviewed, I argue for the latter.

School Phone Bans: Are We Solving the Wrong Problem?

Given the mixed evidence on social media’s harms, you might wonder: what about the practical solutions being implemented? Twenty-one states are now studying or have already enforced school phone bans. Florida led the charge, banning cell phones during instructional time and restricting social media access on school Wi-Fi. Louisiana, Virginia, and Indiana just finished their first year of implementation, while Oklahoma, North Dakota, and New York have bans coming next school year.

The logic seems simple: if phones are distracting students and harming their mental health, removing them should help. But what if we’re missing something crucial about why kids turn to their phones in the first place?

The Myth of the Golden Age of Childhood

Before diving into phone bans, we need to examine the premise behind them. Jonathan Haidt argues we should return to a “golden age” of childhood when children played freely without adult supervision. He describes his own 1960s childhood in suburban Scarsdale, riding bikes and going on neighborhood adventures. Dr. Peter Gray similarly recalls the 1950s, playing pickup baseball and basketball with no adults in sight.

But this “golden age” narrative has some serious blind spots.

Who actually had this freedom?

This idealized childhood was primarily available to White, middle-class boys. Here’s what the research shows about who was actually free to play:

Girls had far less freedom due to cultural expectations that kept them closer to home. Even today, young men and boys spend 85% more time outdoors than young women and girls. In interviews with English girls, many report feeling unwelcome or unsafe in parks when boys are using the spaces.

Black and immigrant children faced segregation and discrimination that made many public spaces unsafe. In 1945, Washington D.C. officially segregated public recreation spaces. Four Black boys were arrested when their ball hit a street lamp outside a park they were barred from entering.

Working-class children often had jobs from young ages. Child labor wasn’t federally regulated until 1938, and many children worked in dangerous conditions in factories and mines.

The “golden age” was golden for some, but it wasn’t universal. And even for those who experienced it, the complete absence of adult guidance had its own problems.

What Actually Happens During Unsupervised Play

While Haidt and Gray celebrate adult-free childhood environments, research shows this freedom came with costs. During recess, one of the few times kids still play with minimal supervision, we see:

- Boys taking over sports fields while girls (and boys who don’t play football) are marginalized

- Racial hierarchies being established and reinforced. Dr. Debra Van Ausdale’s ethnography of preschool classrooms found white children “trying on” the use of power over non-White classmates, seeing if adults would notice or intervene. By and large, nobody did

- Bullying and exclusion of children with less social capital, neurodivergence, etc.

- Boys’ sexual harassment of girls is normalized

These findings suggest that completely unsupervised play doesn’t automatically create the inclusive, character-building environment that phone ban advocates envision.

The Academic Performance Argument Falls Apart

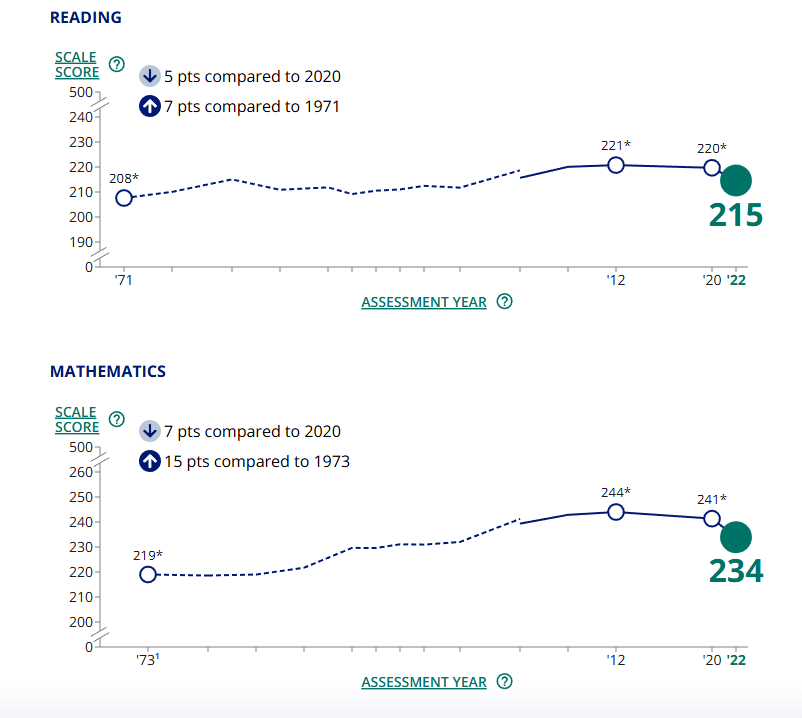

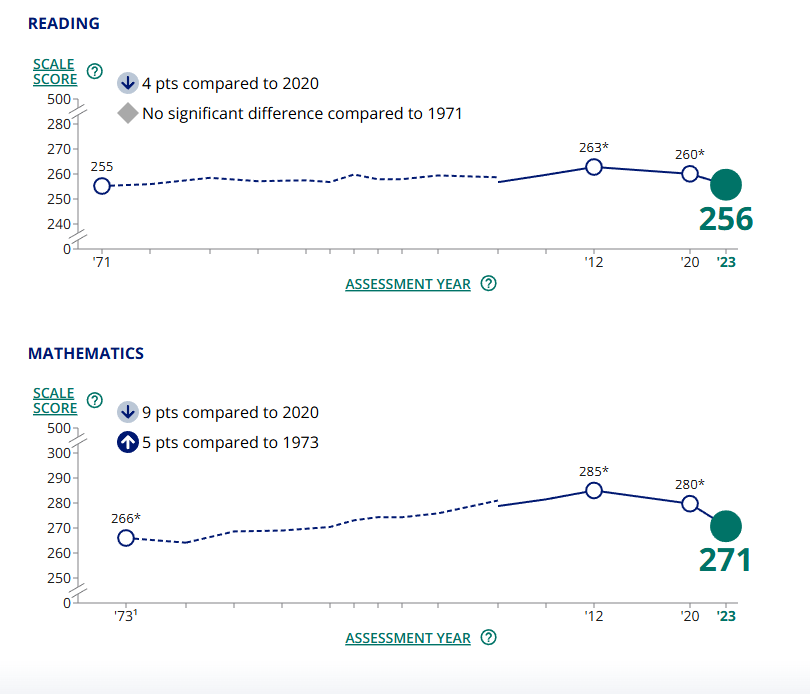

Haidt claims that declining test scores since 2012 prove phones are destroying education. He points to National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) data showing drops in reading and math scores coinciding with smartphone adoption.

But when we look closely at the numbers, the story changes:

The “decline” in test scores is tiny

For 9-year-olds, reading scores dropped by one point from 2012 to 2020 on a scale of 0 to 500. Math scores dropped by three points. (Declines in 2020 and beyond point to COVID as a factor, rather than screens.)

Figure Source: National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP), National Center for Education Statistics, U.S. Department of Education. Retrieved from https://www.nationsreportcard.gov/ltt/?age=9

For 13-year-olds, reading dropped three points and math dropped five points over eight years – again on a scale of 0 to 500.

Figure Source: National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP), National Center for Education Statistics, U.S. Department of Education. Retrieved from https://www.nationsreportcard.gov/ltt/?age=13

These aren’t “substantial” declines – they’re barely measurable changes on a massive scale.

International data doesn’t support the theory

If smartphones were driving academic decline, we’d expect to see them in countries with high smartphone adoption. But when we compare data on smartphone penetration in 2013 and PISA (an international test of student achievement) scores, we find:

- Singapore and Norway maintained or improved their high scores despite high phone penetration.

- The UK, Hong Kong, and Israel had flat or improving trends.

- Sweden hit a low point in 2012, then rebounded (pre-COVID), with a smart phone penetration 8 points higher than the U.S.

- The United Arab Emirates, with the highest phone penetration in 2012, held steady in reading (pre-COVID) and improved in math.

- Australia’s scores have declined linearly, a trend which began well before 2010 (first smart phones) / 2012 (front-facing camera/Instagram) / 2013 (first smartphone penetration data available).

While we have to assume that smartphone penetration was similar for adults and teens (as separate data on teens isn’t available), there’s no consistent pattern linking high smartphone penetration to academic decline.

Other factors driving school outcomes were ignored

Haidt ignores that both Common Core standards and the Race to the Top program were implemented in 2010, exactly when he claims phone-related decline began. These programs cost $10-20 billion federally plus billions more at state level, fundamentally changing how teachers taught and students learned. Research indicates that these programs (especially Common Core) have not improved students’ learning outcomes, and may have done harm.

It’s unlikely that disengagement with school, or test score performance, is driven solely, or even mostly, by kids’ mobile phone use. So is banning phones in school the right answer?

What Research on School Phone Bans Actually Show

The research on phone bans in schools reveals mixed results at best:

Denmark: Mixed results on physical activity from a not-real ban

- Only 68% of students actually complied with the “ban” (so was the study even a real test of smartphone bans?)

- There were no control schools that didn’t ban phones for comparison

- The study occurred during COVID with various outdoor recess mandates, which could have affected the results

- Four weeks isn’t long enough to determine lasting effects

England: No significant differences (probably driven by study design)

Researchers compared 30 schools with restrictive versus permissive phone policies and found no significant differences in:

- Student mental wellbeing

- Anxiety or depression

- Academic achievement

- Disruptive behavior

- Sleep or physical activity

The “restrictive” schools often still allowed phones in bags or lockers, and while in-school phone use decreased, overall daily usage didn’t change – suggesting kids just used phones more outside school.

Industry-supported study: Miraculous results!

Yondr, the company that makes locking pouches for phones commissioned a study showing dramatic improvements in academic success and behavior. But this “research” had:

- No control group

- No accounting for other variables that might affect outcomes

- Marketing-style displays of data rather than rigorous analysis

- A clear financial conflict of interest

What this means for you: If your child’s school bans phones, don’t expect it to dramatically improve their mental health or grades. Research suggests these bans treat symptoms rather than causes. Stay focused on what actually helps your child do well: feeling connected, having some control over their life, and dealing with real stress they face.

A Teacher’s Story Reveals the Real Problem

The most revealing insight for me came from physical education teacher Gilbert Schuerch, whose account of his school’s phone ban was featured on Haidt’s blog. Schuerch describes the elaborate lengths students went to circumvent phone restrictions:

- Stabbing through the Yondr pouches with pens

- Bringing two phones (one decoy to put in the Yondr pouch; one real to keep in their pocket)

- One enterprising student bought the Yondr unlock magnet on Amazon and charged classmates $1 per unlock

But the most telling part is Schuerch’s typical interaction with a disengaged student. When a student doesn’t want to participate in gym class, Schuerch tells them:

“You have to learn how to do the things you don’t want to do… Here’s what I actually want right now. I want to be home, on my couch, watching Netflix, with a girl on my left arm, and a girl on my right… But here I am, because we have to do the things we don’t want to do.”

Setting aside the teacher’s sexist dream that he’s holding up as a model to his student, and also that the teacher’s own dream involves zoning out in front of a screen even as he’s telling his student to engage in the class.

What’s most important to me is that Schuerch sees the main purpose of school is to train kids to do things they don’t want to do, so they can spend the rest of their lives doing things they don’t want to do.

Is this really the purpose of school? Is this what we hope our kids will aspire to in life?

The Missing Piece: Why Kids Want Phones

This exchange reveals what phone ban advocates miss: kids turn to phones because phones meet needs that school doesn’t. Kids turn to their phones to meet needs like:

- Autonomy: Choice over what to engage with and when

- Connection: Real relationships with peers on their terms

- Relevance: Content that feels meaningful to their lives

- Agency: The ability to shape their own experience

School, by contrast, often provides:

- Forced compliance with predetermined curricula

- Limited choice in activities or pace of learning

- Minimal opportunity for authentic peer connection

- Content disconnected from students’ interests and experiences

When we ban phones without addressing these underlying needs, we’re treating symptoms while ignoring the underlying disease.

What Students Actually Say About School Engagement

When researchers ask teens directly about school engagement (instead of just studying numerical data), students report that engagement is fostered by:

- Supportive relationships with teachers and staff

- Opportunities for real choice and voice

- Relevant, hands-on learning experiences

- Classroom environments focused on growth rather than just grades

- Respect and fair treatment from adults

School disengagement is associated with:

- Strict, punitive rules and policies (perhaps including phone bans?)

- Irrelevant or boring curriculum

- Limited autonomy and voice (perhaps on policies like phone bans?)

- Lack of respect from adults

- Peer exclusion and social problems

Some researchers in Spain worked with middle schoolers in several different schools to co-design ethnographic research on the middle school experience. One student said:

“I learn little in school. I spend most of my time looking for information … I look for things not explained at school in Internet … [ … ] In the class, I listen, but not too much, because just being attentive you get the picture. I know too much…I learned to produce videos, movies, songs … The camera … I know a lot about videos: effects, how to assemble a video, and so on.”

An adult researcher on the project observed:

“What the students learn in school somehow helps them to understand the outside world, but what they learn outside is not usually incorporated and taken into account at school. Only in a very few classes teachers pay attention to their experience, knowledge and understandings. At school they learn things to pass exams, but once passed they find difficult to remember them. They tend to remember what they learn outside, because for them this learning is more meaningful, is more related to their experiences, interests, and social and emotional relationships. Although digital technology is increasingly incorporated in classes, it is used differently inside and outside school. Within often its use places them as spectators and recipients of information, outside its use increases their responsibility, agency, ability to scan information, to communicate and express.”

Phone access might be related to school disengagement, but it’s only a small part of what drives disengagement. Relationships, relevance, and respect are what matter. Where teachers and schools can build real relationships with kids, kids thrive. When kids know that their voice doesn’t matter, and that the adults are trying to get kids to do things that don’t matter, kids disengage.

Phone bans are unlikely to lead to a huge improvement in kids’ mental health (since they may just use their phones more outside of school) or test scores. Fortunately this will be relatively easy to test: in a year or two, we’ll expect to see kids’ mental health and test scores increasing in the states where bans have been implemented.

What this means for you: If your teen seems checked out from school, their phone probably isn’t the main problem. Look for signs they feel unheard, overwhelmed, or disconnected from learning. The solution likely means pushing for better school experiences, not just taking away their device.

Now we’ve looked at schools, what should we do about our kids’ use of smartphones and social media at home?

Should We Ban Our Kids from Using Smartphones at Home?

Dr. Jean Twenge, Jonathan Haidt’s frequent collaborator, will release a book in September 2025 offering what seems like the perfect solution: 10 Rules for Raising Kids in a High-Tech World: How Parents Can Stop Smartphones, Social Media, and Gaming from Taking Over Their Children’s Lives.

Her rules include “You’re in charge,” “No social media until 16,” and “Give the first smartphone with the driver’s license.”

These rules are appealing to parents. They’re clear, easy to communicate, and give us something concrete to do. But what if this approach, built on control and restriction, actually pushes our kids further away from us when they need our guidance most?

The Problem with “You’re in Charge”

Twenge’s Rule #1 is “You’re in charge.” While I understand the appeal of parental authority, especially when dealing with apps designed to capture our kids’ attention, this approach has a fundamental flaw: it’s really hard to change someone else’s behavior.

Nobody likes it when others try to control their behavior, and kids are no exception. When we make ourselves “in charge” of our teen’s technology use, we’re essentially trying to control their behavior rather than helping them develop their own internal compass.

Here’s a personal example: My husband loves mountain biking and has been encouraging our daughter to ride with him for years. Despite his enthusiasm and constant invitations, she increasingly resists. The more she’s asked to ride, the less she wants to do it because she wants it to be her own decision.

Contrast this with hiking, something I love but stopped pushing her to do. Once I gave up asking, she started occasionally suggesting hikes herself. She wants to make choices about her own activities, just like she chooses to walk dogs for her pet-sitting business. She doesn’t love walking, but she does it because she chose the goal of building her business.

What this means for you: Rules and restrictions might seem like the obvious solution. But, they often backfire by damaging the trust and communication you need most. Before implementing strict limits, ask yourself: Am I trying to control my teen’s behavior, or am I trying to help them develop their own healthy relationship with technology?

Why Control-Based Approaches Backfire

The sneaking problem

When we ban technology, kids don’t just comply. They get creative. They already know how to:

- Create secret social media accounts

- Hide social media app icons behind calculator logos

- Access devices at friends’ houses

The real danger isn’t that they’ll only reduce their screen time slightly when we take their phone away (which Twenge says is still beneficial). The danger is that they’ll lose the ability to come to us when they encounter disturbing content, inappropriate contact, or confusing situations online.

Imagine two scenarios:

Scenario 1: A teen with open dialogue about technology encounters disturbing content on their device and thinks: “I saw something online that made me uncomfortable. I’m going to tell my parent so I can understand this better and make a plan so I don’t see that kind of content again.”

Scenario 2: A teen who’s banned from smartphones sees the same content on a friend’s device but thinks: “That’s really disturbing. But my friend says it’s normal, so I guess it must be normal. I can’t tell my parent about this because I’m not supposed to be on a phone at all and they’ll kill me if they find out.”

Which teen is safer?

The historical failure of “Just say no”

We’ve tried control-based approaches before. The Drug Abuse Resistance Education (DARE) program in the 1980s and 1990s taught kids to “just say no” to drugs through willpower alone. Not only did DARE fail to reduce drug use, in some cases, it actually increased it.

- It promoted abstinence without addressing underlying reasons kids use drugs (stress, trauma, curiosity, social pressure)

- Zero-tolerance messaging discouraged honest conversations

- Kids knew they’d be punished if caught, so they couldn’t seek help

Sound familiar? Kids use social media for many of the same reasons they might use drugs. They use it to cope with stress, connect with others, escape boredom, or explore identity. When they thought about using drugs or actually tried them, they didn’t talk with caring adults because they knew they’d be in trouble.

The Relationship Cost of Control

When we focus primarily on controlling our teen’s behavior, we risk damaging the very relationship that could help them navigate technology healthily. Consider this story from the book Hold On To Your Kids by Gordon Neufeld and Gabor Maté:

Melanie was thirteen years old. Her father could barely contain his anger when he talked about his daughter. Life with her changed after Melanie’s grandmother had died when the child was in the sixth grade. Until that time, Melanie had been cooperative at home, a good student at school, and a loving sister to her brother…Now she was missing classes and couldn’t care less about homework. She was sneaking out of the house on a regular basis. She refused to talk to her parents, declaring that she hated them and that she just wanted to be left alone…

The mother felt traumatized. She spent much of her time pleading with her daughter to be “nice,” to be home on time, and to stop sneaking out.

The father could not abide Melanie’s insolent attitude. He believed that the solution was somehow to lay down the law, to teach the adolescent ‘a lesson she would never forget.’ As far as he was concerned, anything less than a hard-line approach was only indulging Melanie’s unacceptable behavior and made matters worse. He was all the more enraged since, until this abrupt change in her personality, Melanie had been ‘daddy’s girl,’ sweet and compliant.

Everyone wants Melanie to be ‘nice’ and ‘sweet’ and ‘compliant’ again. Perhaps she was short with them at times in her grief after her grandmother’s death, and they responded by pushing her away.

She withdrew further, so they punished her more. They created a cycle where her friends became more accepting than her parents, and she no longer wants to be with her family.

If the book had been written more recently than 2004, Melanie’s Dad would have shouted at her for always being on her phone, and then taken it away. But would this have improved their relationship? The “solution” of imposing stricter rules doesn’t address why Melanie pulled away in the first place. It just continues the pattern that created the problem.

What this means for you: The relationship you have with your teen matters more for their mental health than any rule you could make about their phone. If screen time restrictions are causing constant fights and pushing your child away from you, the cure might be worse than the problem.

What Kids Are Really Moving Away From

Here’s something crucial to understand: when kids spend excessive time on screens, they’re not just moving toward technology. They’re often moving away from something, and sometimes that thing is us.

Many teens become what Neufeld and Maté call “peer-oriented”. They are more attached to their friends than to their parents. While cutting off screen time might seem like it would bring them back to us, it won’t work if we haven’t addressed why they moved away in the first place.

If your relationship with your teen has become primarily about rules, consequences, and compliance, removing their phone won’t suddenly create the warm, connected relationship you want. It might just leave them feeling more alone and powerless.

Make Offline Life Compelling

Instead of restricting online activities, we need to make offline experiences genuinely interesting:

- Support kids in taking on real responsibility: My daughter loves her pet-sitting business partly because clients trust her with important things like their pets’ safety and their house keys. (It’s not like we hadn’t tried to get her to take on more responsibility around the house but again, it being self-chosen is key!)

- Acknowledge their contributions: Even for routine chores, acknowledgment matters. Just like adults appreciate being thanked for cooking dinner, kids appreciate recognition for their efforts. I now thank Carys each day for unloading the dishwasher and putting her plates in the kitchen after dinner.

- Support their goals: When Carys wanted to expand her business, she needed pet first aid certification. The online course was miserable. The written content was hard for her dyslexic brain to process. I supported her by showing her how to use a screen reader (which read in a boring monotone). But she persevered because it served her goal, not something imposed on her.

- Create opportunities for autonomy: Let them make meaningful decisions about their classes, schedules, and activities. When we push them into doing things they don’t want to do they might learn a skill, but it might come at the cost of our relationship with them.

What this means for you: If your teen seems “addicted” to their phone, look at what they might be avoiding in real life. Are they stressed about school? Feeling disconnected from family? Bored with their daily routine? Address the underlying issue, not just the symptom.

Moving Forward: 6 Strategies Better Than Just Banning Phones

I’m not directly facing challenges with phones or social media yet, because Carys doesn’t use either of them by her choice. I still use the following strategies around discussions about iPad time.

Instead of focusing solely on restriction, I hope you’ll consider involving your kids in any rules around phone usage, model healthy device use yourselves, and address broader sources of stress and disconnection in your family.

Here are strategies that work better than simply banning phones:

Screen time strategy #1: Look at the whole picture, not just the screen

Teen mental health comes from many different places. It can be from school stress, family problems, being excluded by friends. For example, if your teen seems ‘addicted’ to their phone, ask yourself: Are they avoiding homework they find overwhelming? Using social media to stay connected with friends when they feel left out at school? Scrolling to decompress after a stressful day of advanced classes? The phone might be their coping mechanism, not the actual problem.

Social media is just one small piece of this puzzle. When we only focus on phones, we might miss the bigger problems that are really causing our teens to struggle. While the exact mechanisms will be different, kids will face these issues regardless of whether they’re online.

Screen time strategy #2: Build strong connections through listening

The best protection for our teens is having close relationships with parents and other caring adults. Set aside time for real conversations about what’s happening in your child’s life, both online and offline. Listen more than you talk.

Instead of ‘How was school?’, try ‘What was the best part of your day?’. Or ask about something specific that you know your child was looking forward to or was feeling worried about. When they share something from their phone, resist saying ‘You’re always on that thing’. Instead try: ‘That’s interesting, tell me more about that’ or ‘How did you feel about that?’.

Don’t jump in with quick fixes. Instead, help your kids figure out their own solutions to the problems they face.

Screen time strategy #3: Work together instead of just setting rules

Instead of making strict rules or banning things completely, include your child in deciding what healthy limits look like. Help them think about how different activities make them feel. Support them in learning to make good choices about technology on their own. When kids help create the rules, they’re much more likely to follow them.

Here’s what this looks like in practice: Sit down with your teen and say, ‘I’ve been reading about screen time and I’m curious about your perspective. How do you feel after spending time on different apps? Are there times when your phone feels helpful versus stressful? What would healthy phone use look like for our family?’ Then actually listen to their answers and build agreements together.

If you start by threatening to take away their phones, your kids will never tell you when phones are actually causing problems for them.

Screen time strategy #4: Focus on the bigger sources of stress for the most stressed people

Pay attention to the pressure you might be putting on your child about grades, activities, or being “successful”. Sometimes the kids who look like they have everything figured out are actually carrying the heaviest loads. Talk with your kids about what success means to them and what kind of support they need.

Look for signs your child is overwhelmed: Are they staying up late doing homework? Stressed about college applications? Feeling pressure to get perfect grades? Having friendship drama?

Ask what support your child would like to receive from you. Maybe that means talking to teachers about workload, helping them develop better study habits, or simply acknowledging that things are hard for them right now.

Look for ways to make the biggest difference. It can be making sure your child supports LGBTQ teens at school or helping young men access resources when they’re struggling. Both of these are likely to reduce the rate of harm more than keeping middle class White girls off social media.

Screen time strategy #5: Create phone-free connection opportunities that don’t feel like rules

Instead of declaring ‘no phones at dinner’, try ‘I miss talking with you. Do you want to cook together tonight?’

If your teen loves a particular game, TV show, or YouTube creator, engage with their interests. Ask genuine questions about what they’re watching or playing.

You might be able to find a shared project to work on, like learning to make sourdough bread, planning a family trip, or working on a room makeover. When you’re both invested in the outcome, phones naturally take a backseat.

When I’m helping my daughter with her business to help other kids start their own businesses we are often using screens. But, there’s a big difference between social media scrolling and recording videos, updating her website, and managing her retirement savings account.

Timing matters: Don’t try to create connection when your teen is stressed, tired, or in the middle of something important to them. Pay attention to when they seem most open. They may need time alone to decompress after school. Dinner might have become a battleground. A quiet late evening or weekend may be a better opportunity.

Make it low-pressure: The goal isn’t deep emotional conversations every time. Sometimes connection can happen by just being in the same room doing different things. It can also happen by sharing a funny meme or having them help you figure out why the printer isn’t working. These small moments build trust that makes the bigger conversations possible.

Follow their lead: If your teen starts telling you about something, put down whatever you’re doing and listen, even if it’s not a convenient time.

The magic happens when your teen starts thinking: ‘I want to tell my parents about this’. Not ‘I have to talk to my parents because they’re making me put my phone away’.

Screen time strategy #6: Remember that every child is different

What helps one child might not help another. For some kids, social media causes stress. For others, it’s where they find important support. For many kids, social media can be supportive in one moment and a stressor in the next.

Think about your child’s personality and what they’re dealing with when making decisions (with them!) about screen time. If your child seems really affected by social media, talk with them about what you’re seeing and ask what help they want. And if your teen is using social media to cope with real-life problems, you’ll need different strategies to support them.

Final Thoughts

The Anxious Generation has received a lot of publicity. A lot of parents are worried about the ideas in the book. This matters because if we believe smartphones and social media cause our children’s problems when they really don’t, we’ll take actions that might not work. They might even be harmful.

The research shows us that social media does influence our kids’ mental health. But a far bigger influence on kids’ mental health is the relationships, pressures, and experiences in their real lives. This doesn’t mean phones are harmless or that we should ignore concerning behaviors. But it does mean that banning devices without addressing the deeper issues is like taking away a teenager’s diary because they’re writing sad entries in it.

Instead of asking “How do I get my kid off their phone?” we might ask:

- “What is my child getting from their phone that they’re not getting elsewhere?”

- “What pressures are they facing that I might not fully understand?”

- “How can I create more opportunities for real connection and meaningful conversation?”

- “What kind of support does my child actually want from me?”

The teens who are struggling most need us to be curious, not controlling. They need us to listen without immediately jumping to solutions. They need to know they can tell us when something online bothers them without worrying we’ll take their devices away.

I know this approach can feel more difficult than simple rules. It would be so much easier if we could just ban smartphones and solve our kids’ problems. But the evidence tells us that the issues our teens face are more complex than any single solution can address.

Our kids are growing up in a world we didn’t experience. Whether we like it or not, technology will be a part of their lives. The question isn’t how to protect them from that reality. It’s how to help them develop the skills and judgment to handle it well.

That happens not through control, but through connection. Not through fear, but through trust. Not by solving their problems for them, but by supporting them as they figure out their own solutions.

Your relationship with your teen is the most powerful tool you have for supporting their mental health. It’s worth protecting, even if it means taking a more nuanced approach to the phone in their pocket.

Frequently Asked Questions About The Anxious Generation

- What is the summary of The Anxious Generation?

Jonathan Haidt’s book says that between 2010-2015, smartphones and social media created a mental health crisis among teens. He says phones replaced “play-based childhood” with “phone-based childhood.” He presents dramatic statistics showing increases in depression, anxiety, and self-harm. But when you look closely, these increases may come from cherry picked research, better mental health screening, and changes in how mental health problems are reported. They may not be new cases caused by technology.

- How do you define a mental health crisis?

A true mental health crisis would show big, consistent increases in problems across different groups and countries. What we actually see are changes that happen inconsistently both within and across countries. For example, suicide rates among kids aged 10-14 increased from 0.8 to 2.2 per 100,000. That rate is still far below middle aged men. It’s also much lower than teens aged 15-19, who tend to spend more time on smartphones and social media than the 10-14 year-olds.

- Why are today’s youth so anxious?

Research shows the biggest factors aren’t social media. These are family relationship problems (cited by 64% of teens seeking help), school pressure, money stress, sleep problems, and school environment issues. Different communities experience stress differently. This is often related to discrimination, poverty, or cultural pressures that have nothing to do with phones.

- Does social media cause depression in teens?

The evidence for causation is much weaker than headlines suggest. Studies claiming to prove this have major flaws: participants know what researchers are studying, effects are measured immediately rather than over time, and many recruit only from middle class, predominantly White communities. The correlation exists but is extremely small. Some researchers argue that the practical significance in real life is much less than for factors like family relationships, friendships, and school stress.

- Should parents allow their child to use social media?

Rather than blanket bans, focus on building strong relationships and open communication. When we ban technology, kids often find ways around restrictions but lose the ability to come to us when they encounter problems online. The real protection comes from having teens who feel safe discussing their online experiences with parents.

- How do you set social media limits with your teen?

Work together rather than imposing strict rules. Include your teen in deciding what healthy limits look like. Help them think about how different activities make them feel. When kids help create the rules, they’re much more likely to follow them and come to you when problems arise.

- Should parents control their child’s phone?

Control-based approaches often backfire. Kids get creative with secret accounts, hidden apps, and borrowed devices. More importantly, they lose the ability to come to you when they encounter disturbing content or inappropriate contact. Focus on connection over control. The relationship is your most powerful tool.

- What’s the best way to support teens’ mental health

Look at the whole picture, not just screens. Build strong connections through listening more than talking. Address bigger sources of stress like academic pressure or family problems. Make offline activities genuinely interesting and support kids in taking on real responsibility and autonomy when they’re ready for it. Remember that every child is different in what they need, and try to meet your child where they are.

- How do I manage my teen’s phone?

Instead of trying to manage the phone, focus on the relationship. Ask what they’re getting from their phone that they’re not getting elsewhere. Listen to their perspective without immediately jumping to solutions. Address any bigger stressors in their life. Create opportunities for meaningful offline connection and real responsibility.

- Should parents have the right to monitor teens’ activity on social media?

Monitoring can damage trust and push teens away when they need guidance most. Instead of surveillance, focus on creating an environment where teens feel safe discussing their online experiences. When they encounter problems, you want them thinking “I can talk to my parents about this” rather than “I have to hide this so I don’t get in trouble.”

Links to products on Amazon are affiliate links, which means I receive a small commission that does not affect the price you pay.

References