How to Deal with Kids Always Asking Why

Key Takeaway

- Children ages 3-5 enter the “Why Phase” when they ask endless questions to understand how the world works.

- Quick Google (or AI) answers teach fact-collecting instead of thinking skills and can actually shut down your child’s curiosity

- Try responding with: “Hmmm…what do you think?” first to engage their reasoning before providing answers and show you value their thinking.

- Turn questions into mini investigations by exploring together rather than jumping straight to final answers – or trying to teach a lesson.

- Let children lead their own learning without forcing teachable moments.

- Their questions build critical thinking, problem-solving, and communication skills that matter more for future success than content knowledge.

- The questioning phase develops lifelong learning foundations and intrinsic motivation – it’s something to celebrate!

You’re barely three sips into your coffee when it starts. “Mama, why is the sky so blue today?” Before you can even formulate an answer, the next one comes: “Why are the birds singing so loud? Why can’t I go swimming right now? Why do we have to eat breakfast when it’s already so hot outside? Why does the sun make everything bright?”

By the time you’ve managed to pour cereal into a bowl you’ve fielded seventeen questions, and you still have the looooong summer day stretching ahead of you.

Nearly every parent of a young child has experienced this at some point – that mix of pride in your child’s curiosity and complete overwhelm at the sheer volume of questions coming your way. (The other parents have kids who rarely ask questions, and we have ideas for them, too!)

Summer seems to make it even more intense, with longer days, less structure, and more time for those little minds to wonder about everything they see, hear, and experience.

Here’s what I want you to know: your child isn’t trying to drive you up the wall (even though it might feel that way). They’re not just asking random questions. They’re actively trying to connect the dots in their world.

The challenge isn’t that your child asks too many questions. The challenge is that most of us were never taught how to handle this phase of development in a way that supports both our child’s growth and our own sanity.

The Science Behind All Those Questions

If your child is between the ages of three and five, you’re in what researchers call the “Why Phase“. While children ask who, what, where, why questions throughout their development, the Why Phase specifically refers to when ‘why’ questions dominate their curiosity.

Around this age, children begin to understand something pretty remarkable: that people have knowledge, and that this knowledge can be accessed simply by asking questions. Think about how sophisticated that realization actually is. Your child has figured out that you know things they don’t know, and that they can get access to that information just by putting their thoughts into words.

This surge in curiosity happens alongside huge leaps in brain development. Language is exploding – not just vocabulary, but the ability to use words to explore ideas. Logical reasoning is emerging, helping them connect cause and effect. And they’re starting to develop what psychologists call “theory of mind“, basically, they’re figuring out that other people have different thoughts and knowledge than they do.

What’s fascinating is that this learning isn’t happening just in their brains. Research shows that we think with our whole bodies through movement, through our hands as we explore objects, through our environment. When your child picks up a stick and examines it while asking about trees, or jumps up and down while wondering about gravity, they’re not getting distracted from learning. They’re actually enhancing it by engaging their extended mind.

I like to think of it this way: your child has turned into a tiny researcher. They notice something that doesn’t fit with what they already understand, they form a guess about how it might work, and then they test that guess by asking you about it. When you give them an answer, they’re not just filing it away. They’re connecting it to other things they know, seeing where it fits in the bigger picture.

The Hidden Problem: Why “Just Answering” Doesn’t Actually Help

When your child asks “Why is the grass green?” your instinct is probably to pull out your phone and ask Google, Alexa, or ChatGPT. Quick answer delivered: “Because of something called chlorophyll.” Question answered, right? You can move on with your day.

But here’s what research shows us: jumping straight to answers can actually do more harm than good. It teaches children that learning is about collecting facts, not exploring ideas. They learn that questions have quick, simple answers that come from others, not from their own thinking.

Imagine giving a quick Google answer about chlorophyll. Your child says, “Oh, okay,” and moves on. But did they actually learn anything meaningful? Probably not. They didn’t explore what chlorophyll does, why plants differ in color, or how it connects to the sun. What they learned is that questions get answered by devices – and they’ll likely forget what you told them in an hour anyway.

This creates answer-seeking behavior instead of thinking behavior. Kids start to believe every question has one “right” answer out there and their job is to find it fast. Curiosity becomes a finish line, not a doorway to discovery.

Here’s the thing that might surprise you: research shows that by the end of first grade, most kids stop asking the rich, wondering questions they asked as toddlers. Instead, they only ask “Do I have to learn this?” and “How do I do this thing you’re telling me to do?” We’ve accidentally trained them out of their inherent curiosity.

But what if we approached their questions differently? What if, instead of jumping in with an answer, we paused to wonder together? This simple shift changes everything. It often means re-examining our own relationship with learning.

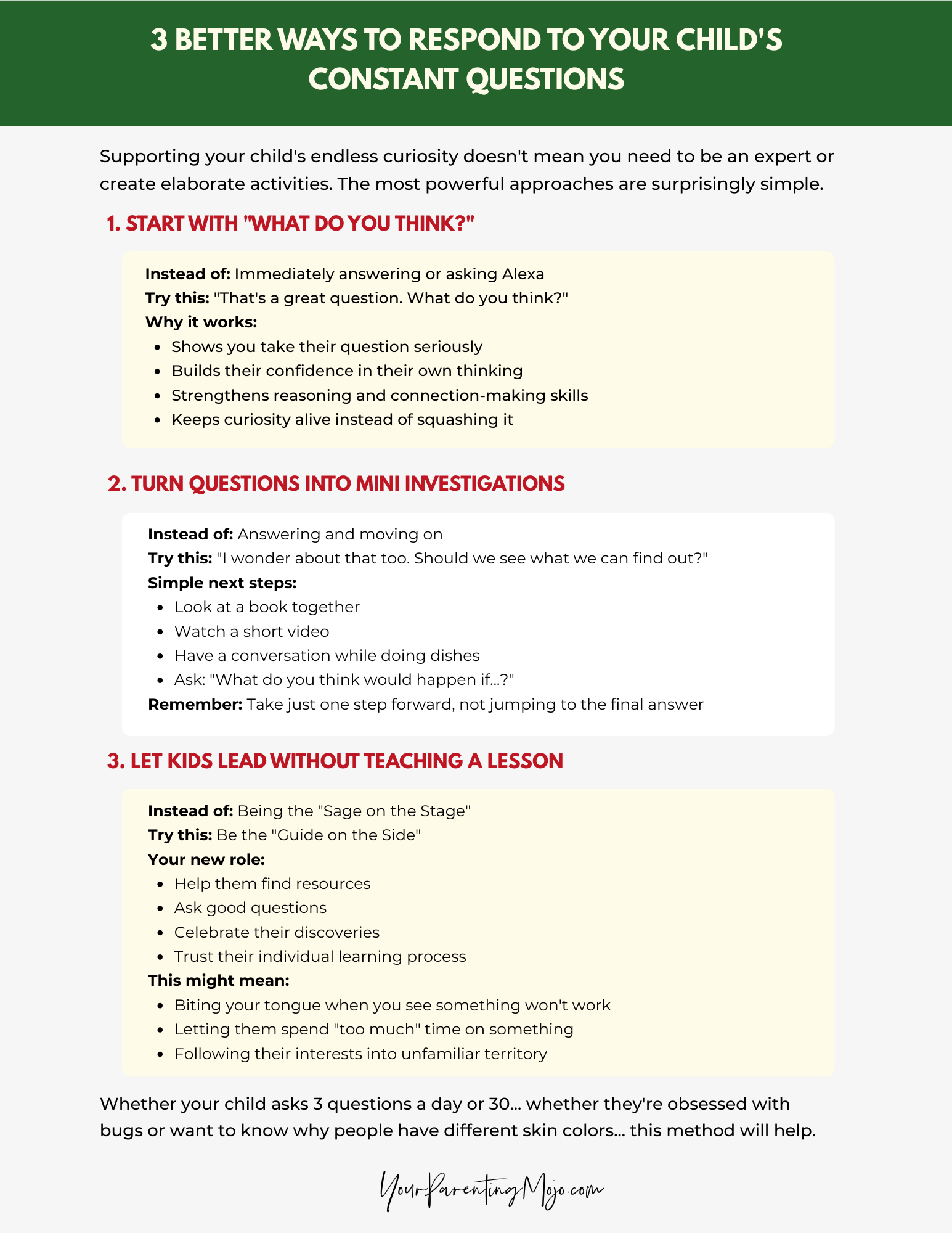

3 More Effective Ways to Respond to Your Child’s Constant Questions

Supporting your child’s endless curiosity doesn’t mean you need to be an expert or create elaborate Pinterest-worthy activities. In fact, the most powerful approaches are surprisingly simple and they work better than traditional ‘teaching’ methods.

Click here to download the 3 Better Ways to Respond to Your Child’s Constant Questions

Responding to your child’s questions #1: Start With “What Do You Think?”

The next time your child asks, “Why is the sky blue?”, pause. Look up at the sky together. And then say something like: “Huh. That’s a great question. What do you think?”

This simple shift is more than just a way to buy yourself a second to think. It tells your child:

- I take your question seriously.

- I believe you’re capable of thinking about this.

- We can explore this together.

This gives your child time to engage their own thinking before being handed an answer. It strengthens their ability to reason, hypothesize, and make connections.

When we respond immediately with facts (or a quick “Alexa, why is the sky blue?”), we accidentally send the message that learning comes from outside themselves and not from within. Over time, that can squash the very curiosity we want to nurture.

Responding to your child’s questions #2: Turn their questions into mini learning investigations

Rather than seeing each question as something to answer and move on from, think of them as launching points for exploration. This doesn’t mean turning everything into a formal lesson. It means following their curiosity one step further.

Here’s what this might look like in real life: When your child asks about why fish live in water, you might say: “I wonder about that too. Do we have any books about fish? Should we see what we can find out?” Or: “What do you think would happen if a fish tried to live on land like we do?”

The key is taking just one step forward, not jumping to the final answer. This is what’s called scaffolding. You provide just enough support to keep your child engaged and learning, but not so much that you take over their thinking process.

Maybe you look at a book together. Maybe you watch a short video. Maybe you have a conversation while you’re doing dishes. The goal isn’t to become experts on fish biology. It’s to show your child that their questions are worth exploring.

Responding to your child’s questions #3: Let kids lead without needing to teach a lesson

This might be the hardest shift for many of us, especially if we went to school ourselves and learned that adults ask questions and children provide answers. But when we let children lead their own learning, they stay engaged much longer and go much deeper than we ever could have pushed them.

Instead of becoming the “sage on the stage,” try being the “guide on the side“. Your job isn’t to lecture about everything you know on the topic (which often makes kids’ eyes glaze over). Your job is more like being a helpful travel companion – someone who helps them find resources, asks good questions, and celebrates their discoveries.

This might mean biting your tongue when they’re building something and you can see it won’t work the way they think it will. It might mean letting them spend way more time on something than you think is “productive.” It might mean following their interests into territory you know nothing about, which, by the way, is perfectly fine.

This kind of trust in your child and in yourself doesn’t always come easily, especially if you went through traditional schooling yourself. Many parents find themselves feeling like their job is to rush and provide answers or resources the moment their child shows interest in something. But learning to step back and trust both your child’s own learning process (and your own instincts as a parent) is often the most powerful thing you can do.

Whether your child asks three questions a day or thirty. Whether they’re obsessed with bugs or want to know why people have different skin colors.

The method stays the same:

- Pause.

- Wonder together.

- Take one step forward.

- And let them lead the way.

Why This Phase Matters More Than You Think

I get it. Sometimes it can feel like you’re trapped in an endless loop of questions from your child.

But here’s what I want you to know: those questions aren’t just something to endure until your child grows out of this phase. They’re actually building the exact skills your child will need to thrive in the future.

When your child seems compelled to ask all these questions throughout the day, they’re not just being curious. They’re developing critical thinking skills.

When I looked into what skills will actually matter for our children’s success, I found something surprising. A McKinsey report identified 56 critical skills for the future job market. Want to guess how many had to do with coding or technology?

Eleven. Just eleven out of 56.

The other 45 skills? Things like critical thinking, communication, self-awareness, and problem-solving. In other words, exactly what your questioning child is practicing right now. While schools focus heavily on content knowledge, these other skills are primarily developed through the kinds of interactions you’re having at home every single day.

The Hidden Skills Behind Your Child’s Endless Questions

When your child fires off what seems like their millionth question of the day, “Why do dogs wag their tails?” followed immediately by “What makes the sky blue?”, it’s easy to feel like they’re just trying to drive you to distraction. But something much more important is happening.

Your child isn’t just hunting for random facts. They are developing the thinking skills they will need throughout their lives. Every time they notice something and wonder about it, they’re strengthening their ability to see patterns and make connections. When they ask why water freezes or how birds know where to fly, they’re doing the same work scientists do, trying to make sense of the world around them.

And when they keep asking follow-up questions? That’s not them being difficult. That’s their way of exploring ideas from different angles and learning to think flexibly.

Perhaps most importantly, when your child follows their own curiosity, they’re learning to set their own learning goals and stick with them, even when understanding gets challenging. These are the foundations of intrinsic motivation that will serve them far better than any external reward system ever could.

The questioning phase isn’t something to survive. It’s something to celebrate – because it’s building the very foundation of lifelong learning.

What to say when kids keep asking why?

Not all ‘why’ questions are equal…sometimes your child will just ask ‘why’ endlessly, even when it doesn’t seem like they’re trying to understand:

Child: Why are we going to Grandma’s house?

You: Because we haven’t seen her since last week.

Child: Why?

You: Because we’ve been busy.

Child: Why?

Your child has discovered a new tool for connecting with you! Very often, these kinds of questions are a way to prolong the conversation, rather than get information. If you sense this is happening, try getting down on their level and asking: “It seems like you’d really like to connect with me right now. Is there something you’d like to do together?” or “Would you like a hug?” (depending on how much time you have available).

In the Learning Membership we call this ‘looking for the question underneath the question: this child isn’t really asking about Grandma; they’re asking for time with you.

If Your Child Isn’t Asking Questions

If your child isn’t asking many questions, that doesn’t mean they’re not curious. They might just be showing their curiosity differently.

Some children are more hands-on learners who prefer to explore through doing rather than asking. Others might be processing quietly, taking in information before they’re ready to wonder out loud.

The key is to become a detective of your child’s interests by watching what they gravitate toward during free time. What do they choose to do when you’re not directing their activities? What lights them up when you suggest it?

Parent Anne discovered this when she sat with a notebook and observed her son’s LEGO play, realizing there was “SO MUCH going on”. He was working through ideas about solar power and movement that she’d never noticed before.

Try sitting quietly and watching your child for just five or ten minutes during their play. Notice what captures their attention, what they return to again and again, what makes them lean in with focus.

Then you can gently offer related experiences: “I noticed you’ve been really interested in how water moves. Want to see what happens when we pour it through different things?” This approach meets children where their curiosity already lives, rather than trying to manufacture interest in topics that don’t resonate with them.

Final Thoughts

When your kids ask you question after question, try to keep your eye on how amazing this stage of your child’s development is! Their questions are a window into how your child’s mind works.

You don’t need to become Google/Alexa/ChatGPT in human form. You don’t need to craft perfect educational moments with Pinterest-worthy setups. What your child really needs is to know that their questions matter to you and that their curiosity is seen and valued.

You also don’t have to have the answers to every question they ask. Your job is to show your child that their questions matter, and that thinking together is more valuable than knowing everything.

Instead of feeling drained by constant questions, you start noticing the incredible mind at work behind them. Your child learns that their curiosity matters. They develop confidence in their own thinking. And you get to rediscover the world through their eyes – which, honestly, is pretty magical.

Those questions aren’t interrupting your day. They’re showing you exactly how to connect with the remarkable little person you’re raising.

Transform those daily questions into meaningful learning moments

If you want more support turning your child’s everyday curiosity into meaningful learning without pressure, lectures, or constant Googling, my ‘You Are Your Child’s Best Teacher masterclass’ can help. It gives you practical tools to turn everyday curiosity into rich learning and connection without lectures, pressure, or overwhelm.

You’ll discover how to:

- Support your child’s intrinsic curiosity (without becoming their personal Googler)

- Turn everyday moments into rich learning opportunities

- Help your child develop confidence as an independent thinker and learner

- Navigate challenging phases (like constant questioning) with understanding instead of exhaustion

- Build your relationship while supporting their development

Click the banner to learn more and sign up.

Frequently Asked Questions About Kids’ Endless Questions

1. Why does my child constantly ask questions?

Your child isn’t trying to drive you crazy. They’re in the “Why Phase” (typically ages 3-5) when their brain is developing critical thinking skills. They’ve realized that other people have knowledge they can access by asking questions. This constant questioning shows they’re connecting dots in their world, developing language skills, and building the foundation for lifelong learning.

2. How to deal with kids asking why?

Instead of jumping straight to answers, pause and ask “What do you think?” first. This strengthens their reasoning abilities and shows you value their thinking. Turn their questions into mini investigations by saying “I wonder about that too” and exploring together. Let them lead the learning process rather than lecturing with facts.

3. At what stage of development does the child ask many questions?

The Why Phase typically occurs between ages 3-5 when children experience huge leaps in brain development. During this stage, language explodes, logical reasoning emerges, and they develop “theory of mind” – understanding that other people have different thoughts and knowledge. This is when “why” questions dominate their curiosity about the world around them.

4. What to say when kids keep asking why?

Try responses like “That’s a great question – what do you think?” or “I wonder about that too. Should we see what we can find out?” Take one step forward in exploration rather than jumping to final answers. This scaffolding approach provides just enough support to keep them engaged without taking over their thinking process.

5. Why is children’s curiosity valuable to learning?

Children’s questions build exactly the skills they’ll need for future success. Research shows 45 of 56 critical future job skills involve critical thinking, communication, and problem-solving – not just content knowledge. When kids ask questions, they’re developing pattern recognition, flexible thinking, and intrinsic motivation that serves them better than any external reward system.

6. How to help kids answer why questions?

Don’t rush to provide answers yourself. Instead, help them explore by asking follow-up questions, looking at books together, or having conversations during daily activities. Be a “guide on the side” rather than “sage on the stage.” Trust their learning process and follow their interests, even into territory you know nothing about.

References

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1985). Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behavior. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4899-2271-7

Dondi, M., Klier, J., Panier, F., & Schubert, J. (2021, June 25). Defining the skills citizens will need in the future world of work. McKinsey & Company. https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/public-sector/our-insights/defining-the-skills-citizens-will-need-in-the-future-world-of-work

Engel, S. (2011). Children’s need to know: Curiosity in schools. Harvard Educational Review, 81(4), 625–645. https://doi.org/10.17763/haer.81.4.h054131316473115

Frazier, B. N., Gelman, S. A., & Wellman, H. M. (2009). Preschoolers’ search for explanatory information within adult-child conversation. Child development, 80(6), 1592–1611. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01356.x

Gopnik, A. (2012). Scientific thinking in young children: Theoretical advances, empirical research,and policy implications. Science, 337(6102), 1623–1627. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1223416

Kuhn, D. (2000). Metacognitive development. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 9(5), 178–181. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8721.00088

Lumanlan, J. (2024). The skills your child will need in the age of AI. Your Parenting Mojo.

https://yourparentingmojo.com/captivate-podcast/ai/

Lumanlan, J. (2023, July 16). How to learn way beyond ‘doing well in school’. Your Parenting Mojo. https://yourparentingmojo.com/captivate-podcast/beyondschool/

Lumanlan, J. (2022, September 11). Learning to trust your child – and yourself. Your Parenting Mojo. https://yourparentingmojo.com/captivate-podcast/claire/

Lumanlan, J. (2021, September 5). The Extended Mind with Annie Murphy Paul. Your Parenting Mojo. https://yourparentingmojo.com/captivate-podcast/extendedmind/

Lumanlan, J. (2020, December 17). Doing Self-Directed Education. Your Parenting Mojo. https://yourparentingmojo.com/captivate-podcast/freepeople/

Lumanlan, J. (2016, September 26). How to “scaffold” children’s learning to help them succeed. Your Parenting Mojo. https://yourparentingmojo.com/captivate-podcast/005-how-to-scaffold-childrens-learning/

Schulz, L. (2012). The origins of inquiry: Inductive inference and exploration in early childhood. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 16(7), 382-389. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2012.06.004

Wang, X., Wang, C., Ye, P., & Tao, G. (2025). The role of intrinsic motivation in enhancing deep learning in early childhood education: Intrinsic motivation and deep learning in ECE. International Theory and Practice in Humanities and Social Sciences, 2(6), 274-290. https://doi.org/10.70693/itphss.v2i6.847

Wellman, H. M., Cross, D., & Watson, J. (2001). Meta-analysis of theory-of-mind development: the truth about false belief. Child development, 72(3), 655–684. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8624.00304