Why Halloween Candy Rules Don’t Work (And What Actually Does)

Key Takeaways

- Why do Halloween candy rules cause fights between parents and kids? Kids want autonomy over decisions that seem important to them, indulgence in delicious treats, and belonging with their friends. But parents worry about children’s health, which can create conflicts.

- Is sugar actually addictive for children? Research shows kids prefer sweetness more than adults. But restriction often creates obsession rather than true addiction.

- What really happens when kids eat too much candy? Most effects are mild (constipation, moderate energy spikes) rather than the extreme hyperactivity parents often fear.

- How can I tell if my candy rules aren’t working? Watch for sneaking behavior, constant negotiation, obsessive focus on rules, or binge eating at parties.

- What works more effectively than strict candy limits? Work together with kids using a collaborative approach. Start with understanding needs, create agreements you both actually agree to, plan scenarios, and adjust.

- Should I allow candy every day during Halloween season? Focus on reducing restriction feelings and building autonomy rather than perfect dietary compliance.

- How do I build a healthy long-term relationship with treats? Prioritize trust and shared decision-making over control.

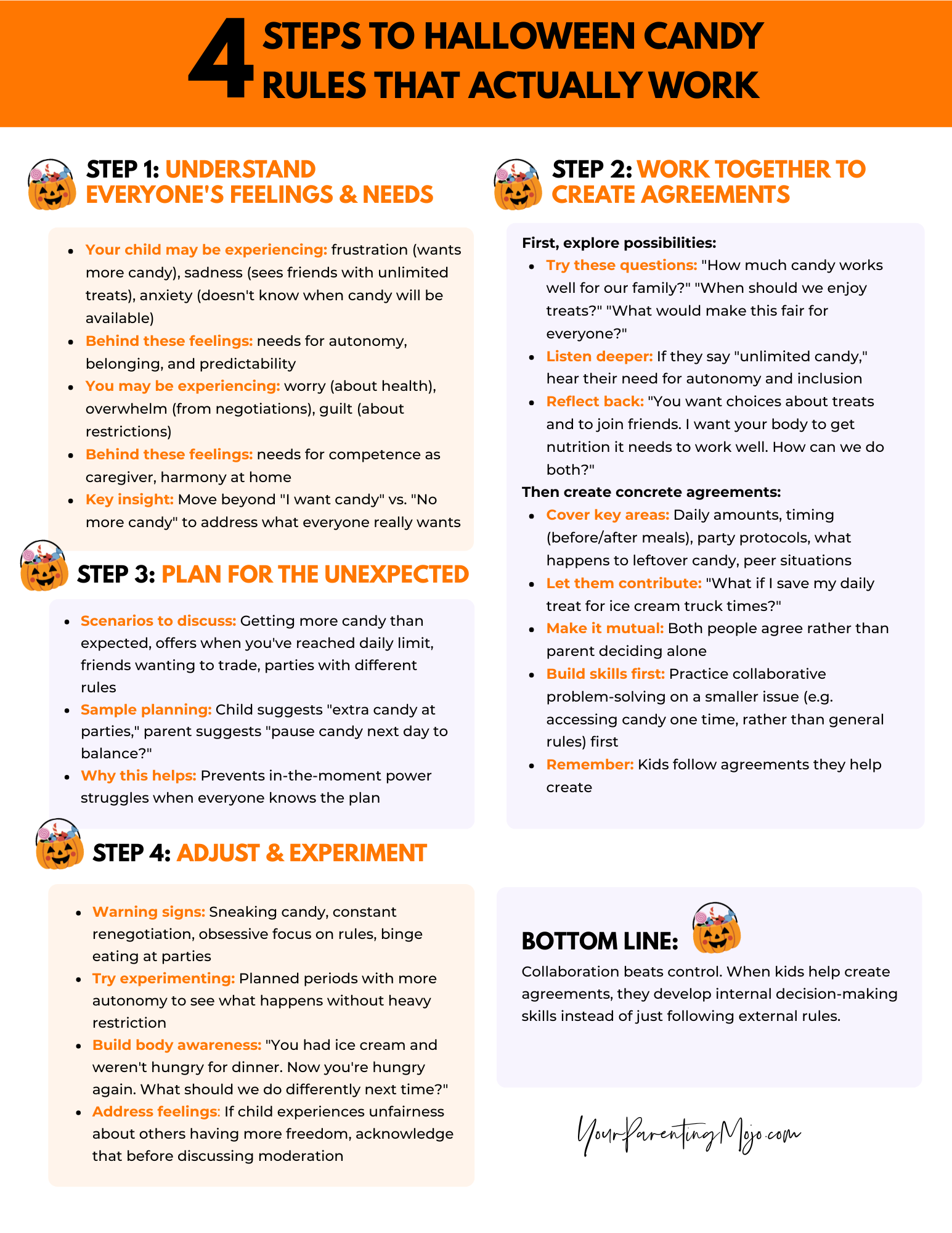

The Healthy Approach to Halloween Candy: Four Steps to Halloween Candy Agreements That Stick

This research-backed four-step process that supports your child in understanding their own bodies and developing internal decision-making skills around treats. Read on for the science that supports this method and step-by-step implementation details.

Click here to download the 4 Steps to Halloween Candy Rules That Actually Work

How Most Halloween Candy Rules Miss the Point

Why does Halloween turn even the most confident parent into someone making deals with a tiny sugar-loving boss?

Every October, parents suddenly find themselves fighting with their kids about candy rules. While parents worry about Halloween candy hurting their kids’ health, the real problem isn’t what happens when you eat too much candy. It’s the fights that rip through families faster than kids can open Fun Size Snickers.

This challenge gets right to the heart of parenting. We worry about what too much sugar does to our kids’ bodies while our kids only see us being ‘mean’ and ‘unfair.’ We want to keep them safe, but our rules often blow up in our faces and create sneaking behavior – or at the very least, a lot of arguments.

Halloween originated as a festival to mark the end of summer and start of winter; the transition between the living and the dead. We’ve changed it to focus much more on decorations and candy. When you think about it, celebrating a holiday so focused on candy and then denying our kids access to this candy must be pretty confusing for them!

Moving beyond these yearly battles requires understanding why traditional Halloween candy rules fail. We can learn from my conversations with Dr. Michael Goran, co-author of Sugarproof, sociologist Dr. Karen Throsby who studies sugar’s social meanings, and parent Rose navigating daily candy battles with her child. Together, we can find a way that respects both our kids’ right to make choices and our job as parents.

Why Halloween Candy Rules Create Such Big Problems

Halloween candy fights happen when parents and kids have different underlying needs. When we understand what everyone really needs, we can find ways that work for the whole family.

Children often have a need for autonomy – they want some control over their own choices. They find candy delicious, and want to indulge in treats they enjoy. They also have a need for belonging and inclusion, especially when they see friends freely enjoying – and maybe even trading – Halloween treats.

Parents usually need competence in taking care of their kids’ health and wellbeing. We need a sense of safety and competence about our kids’ future relationship with food. We also don’t want endless fights with our kids! We have needs for ease and harmony.

Many parents also have a deep need to feel competent as caregivers – to know we’re supporting our children’s wellbeing in ways that align with our values. When we worry about candy, we’re often experiencing fear that something harmful might happen if we don’t step in. This fear can drive us toward trying to control the situation, but what we’re really seeking is confidence that our children will be okay and that family life can flow with more ease.

Conflicts intensify because Halloween candy carries deep cultural meaning beyond nutrition. As Dr. Throsby explains, sugar is tied up with fun, love, celebrating, and eating with other people. When we create rigid rules around Halloween candy, we’re inadvertently asking children to separate the treat from the social connection and celebration it has come to represent.

The traditional approach – where parents make the rules, while kids are expected to follow them – doesn’t meet anyone’s needs well. Kids’ needs for autonomy and inclusion stay unmet, while parents’ needs for ease harmony in the house also don’t get fulfilled.

Can Sugar Be Addictive?

A lot of our worry about Halloween candy comes from hearing that sugar is addictive. Dr. Throsby studies how people talk about sugar in news stories and health messages. She says that when we call sugar “addictive”, it makes us panic and think we need to do something right away, but it doesn’t actually fix the real problems.

When parents hear that sugar might be addictive, it can trigger our need for competence as caregivers. We want to feel confident that we’re protecting our children from potential harm. This fear of ‘getting it wrong’ can drive us toward rigid control, but what we’re really seeking is the ease that comes from knowing our approach supports both our child’s wellbeing and our family’s harmony.

Dr. Michael Goran studies how much sugar kids eat. His research shows that kids do like sweet things more than grown-ups do. And that built-in preference gets amped up even higher with exposure to sweet foods. But this doesn’t make sugar addictive like drugs or alcohol.

The bigger problem is that when we don’t let kids have something, they usually want it even more. When we control something children enjoy, we might make it seem more special and exciting. This can lead to kids thinking about sugar all the time, and if they know they’re not allowed to have it, they may start sneaking food.

Rose, a parent who shared her story on the Your Parenting Mojo podcast, experienced this firsthand. Despite following expert advice about limiting sweets, she noticed that her daughter had begun hiding sugary food to eat it when her parents weren’t around. The very rules designed to create a healthy relationship with sugar were undermining that goal.

What Happens If You Eat Too Much Candy

Understanding what happens when kids eat a lot of sugar can help us to approach this topic in a way that’s aligned with our values.

Dr. Goran explains that fructose is a big part of many candies. When kids eat it, their liver turns it into fat through a process that causes swelling in the body. This sounds scary, but what parents actually see is often not as bad as they expect.

Real symptoms parents notice include constipation instead of the extreme behavior changes we’re often told about. Sugar can give kids a quick burst of energy, then crash and become hungry and want more sugar. But this isn’t the same as the wild hyperactivity many parents worry about.

We might also worry that kids won’t eat enough nutritious food if they’re eating so much candy. My own daughter has noticed a paradox in how my husband talks to her about candy: if she asks for it before dinner, he says: “Don’t eat candy before dinner, or you’ll be full and won’t eat your meal.” But if she asks for candy at dinner time, he says: “Candy isn’t real food; it won’t fill you up!” Getting clear in our own minds about what we believe can help us to give our kids more consistent messaging.

Signs Your Halloween Candy Rules Aren’t Working

Several red flags indicate that your Halloween candy approach might be creating more problems than it solves:

- Sneaking and hiding behavior suggests your child’s access to candy is overly restricted. When children go hide and eat things, they’re telling us the rules are too hard to follow the way we set them up.

- Constant negotiation around treats creates ongoing stress for everyone. If you’re hearing “Are we having cookies tonight?” followed by tears and upset no matter what you say, the system isn’t working for anyone.

- A heavy focus on candy rules can prevent children from enjoying Halloween activities. When kids worry so much about candy rules that they can’t enjoy other parts of the holiday, our rules are making things worse.

- Going overboard at parties or events might mean the rules at home are too strict. Rose talked about her daughter sitting for two and a half hours eating cookies at a party while other kids played. This showed that the child thought she had to eat as much as possible whenever she got the chance.

If you recognize these patterns in your family, it’s because the restrictive approach that many of us learned about candy isn’t working for us. Here’s a way to create a new relationship with candy for your child.

4 Steps to the Problem-Solving Approach to Halloween Candy Rules

Instead of imposing rules, consider involving your child in creating a Halloween candy plan that works for your family. This approach acknowledges that sustainable solutions need buy-in from everyone affected.

Problem-solving approach to Halloween candy rules #1: Understand everyone’s feelings and needs

When conflicts arise around Halloween candy, both parents and children are typically experiencing real feelings that point to important underlying needs. Taking time to understand these can transform your approach.

Your child might be experiencing frustration when they want autonomy over their treats. Or sadness when they see friends participating freely in Halloween traditions like trading that they can’t be a part of (because they don’t have candy) – they want to belong in their friend group.

You might feel worried about your child’s health and eating, or overwhelmed by regular arguments about food. Your underlying needs might include competence as a parent – feeling confident that you’re supporting your child’s wellbeing – and ease in your daily family life. When we feel uncertain about how to handle candy, we might try to control the situation because we fear something bad will happen if we don’t. But often what we’re really seeking is the confidence that comes from knowing our approach aligns with our values and supports our child’s long-term relationship with food.

And of course, this emotional work often gets dumped on mothers. Dr. Throsby’s research shows that food decisions become “women’s work,” and our performance as mothers is judged by what our kids eat, as well as their body shape and size.

When you can identify the specific feelings and needs involved, you move beyond the surface-level battle of “I want candy” versus “No more candy”. Instead, you can explore creative strategies that address everyone’s underlying needs.

If you’d like help identifying specific feelings and needs in your family’s candy conflicts, you can reference this feelings list and needs list to get more precise about what’s really driving the struggle.

Problem-solving approach to Halloween candy rules #2: Work together to create agreements

Instead of having predetermined Halloween candy rules, shift into a collaborative approach. Invite your child to share their perspective and ideas. This process has two parts: exploring possibilities and then committing to specific agreements.

Start by exploring possibilities together

Invite your child to share their perspective and ideas. Start with open-ended questions that invite creativity. Ask questions like:

“How much candy do you think would work well for our family?”

“When would be good times to enjoy treats?”

“What would make this fair for everyone?”

“How could we make sure you still eat your meals, and don’t feel so amped-up you can’t go to sleep?”

These kinds of questions position you as partners working toward shared solutions.

Listen for the needs behind your child’s initial suggestions. If they say “I want unlimited candy”, you might hear their need for autonomy and inclusion. You can acknowledge those needs while exploring strategies that also meet your needs. You may say: “You want to be able to make choices about your treats and not miss out when friends are having fun. I want to make sure your body gets the nutrition it needs to feel good. Let’s think about ways to honor both of those things.”

Then create concrete agreements

Once you understand each other’s perspectives, work toward concrete agreements. These might include:

- How many pieces of candy per day seems reasonable to both of you

- Whether candy comes before or after meals

- How to handle special occasions or parties

- What happens to the candy stash over time

- How to navigate peer situations where other kids have different rules

The key is that these agreements emerge from your conversation rather than being imposed unilaterally. Your child is more likely to follow agreements they helped create.

A collaborative agreement might sound like: “I want one sweet daily, but I also want to join friends at the ice cream truck. What if I save my daily sweet for those times, or what if we agree on flexible amounts for social situations?”

If your family is new to collaborative problem-solving, start practicing on less emotionally charged issues before tackling Halloween candy, like a request for ice cream or candy on a day before Halloween.

Success in smaller negotiations builds skills and trust for more challenging conversations. Your child learns that their input matter to you. And that you’re genuinely interested in finding solutions that work for everyone.

It’s very important that you don’t go into the conversation with a fixed idea of a single outcome that will work for you (“One piece of candy per day or nothing!”). Your child will sense this inflexibility and will likely refuse to engage.

If you’re new to collaborative problem solving and your child won’t participate, you might say something like: “Last year I made the rules and you didn’t like them. I really think we can find a way to meet both of our needs, and I’m willing to try to do it if you’re willing to participate. If we can’t talk about it then I’ll make the rules again like I did last year, and they might not work for you. I’d prefer not to do that, though, if we can avoid it.”

Your tone of voice can be the difference between making this a threat and an invitation to collaborate, so you might want to practice this in your head before you say it out loud to your kids.

Problem-solving approach to Halloween candy rules #3: Plan for the unexpected

Halloween rarely goes exactly as planned. Discuss scenarios together:

- What if you get way more candy than expected?

- What if someone offers candy when you’ve already had your agreed amount?

- What if a friend wants to trade or share?

- What if you’re at a party with different rules?

Having these conversations beforehand helps everyone be prepared and reduces in-the-moment conflicts.

For example, your child might suggest “I can have extra candy at parties”. You might agree while adding “and could we pause candy the next day to balance it out?” You might find your child is willing to come toward you on the day after the party when you come toward them on the party day itself.

Problem-solving approach to Halloween candy rules #4: Adjust and experiment

People’s needs change, so even perfect collaborative agreements will evolve over time. If you see your child hiding candy or always asking to change the rules, you might want to try something different.

Dr. Goran suggests approaching this as a family experiment. You can see for yourself and record the changes in how your child relates to sweets under different conditions.

During these experiments, help children connect their food choices to how their bodies respond. Comments like “You had the ice cream, and you didn’t become hungry at dinnertime, right? But now you’re super hungry again” help kids develop their own internal awareness rather than relying solely on external rules.

You may also decide to keep a journal for a period of time, recording what your child eats and what else is going on in their lives. Many parents uncover that the bedtime meltdown is less about candy and more about waking up early that morning, or challenges at preschool/school.

When children do overeat, address the underlying feelings rather than just the behavior. If your child wonders why does everyone else get all of this stuff and they don’t, that sense of unfairness needs attention alongside any conversations about moderation.

Help kids understand how their bodies respond to sugar, which may change over time. When my daughter was two, a lollipop given by a kind server at a restaurant led to an hour of running around. Now she’s 11, that same lollipop no longer has the same effect on her.

Long-Term Halloween Candy Health Strategy

When thinking about Halloween candy health over time, sustainable approaches focus on overall nutrition patterns rather than micromanaging individual treats. Dr. Goran emphasizes reducing sugar, increasing fiber, increasing protein, and increasing more fruits and vegetables as general principles. This supports health without creating food anxiety.

One really useful tool that Dr. Goran introduced me to is to offer another food with candy. This can look like:

Child: “Can I have a lollipop?”

Parent: “Yes, although I’m a bit worried you’ll suddenly have a lot of energy and then you’ll crash afterward. Would you like to have some yogurt with it, so you get some protein as well?”

Remember that learning to have a positive, nourishing relationship with food is a lifetime journey for many of us. It will change as you and your child learn together. Halloween is just one part of a much bigger conversation about how your family thinks about food and celebrating.

The goal is helping kids learn what they like and how to make their own choices instead of having parents control everything forever. This means accepting that kids will make mistakes. This also includes Halloween nights when they might eat more candy than you want them to.

Making Peace with Halloween Candy

Is It OK to Eat Candy Every Day? A Realistic Answer

World Health Organization recommendations about sugar focus mainly on dental caries rather than dramatic health effects. This suggests that moderate candy consumption isn’t the emergency we sometimes imagine.

Parent Rose tried allowing “one sweet thing a day” and found it initially helped. But it created new problems when opportunities arose for additional treats. The real question isn’t whether daily candy is “okay” but whether your approach is creating restriction and obsession.

Sometimes it’s better to have more but less frequently. Especially if that approach reduces conflict and sneaking while maintaining overall nutrition goals.

Building a Healthy Relationship with Halloween Treats

Dr. Throsby reminds us that we get a lot of pleasure from eating, – not just via taste, but socially as well. We may struggle with children’s candy intake at Halloween because we see so much enjoyment and indulgence in our kids – but we’ve been continually warned about the ‘dangers’ of eating too much and of eating the ‘wrong’ kinds of food.

It can help to separate out our own feelings about our children’s body shape and size from theirs.

If we choose to celebrate Halloween, we probably hope it will be enjoyable rather than anxiety-provoking. Creating positive associations with celebration and food serves children’s long-term wellbeing.

The path forward is in the direction of autonomy over decision making rather than external control. This means helping children develop internal tools for making food decisions.

We want to raise kids who can make good choices while still enjoying parties and eating with friends.

Final Thoughts

Successful Halloween candy rules prioritize relationships and trust over perfect compliance. This year, try talking with your child about Halloween candy rules before the big day. Ask your child what they think would be fair, what they worry about, and what they want from Halloween.

Giving up some control over what your kids eat may ultimately help you to meet your broader goals for your children’s long-term health and balanced relationship with food.

Remember that your need for competence as a parent is valid. You want to feel confident that your approach supports your child’s wellbeing. The collaborative method honors this need while also meeting your need for ease in daily family life – reducing the exhausting negotiations that rigid rules often create.

Most importantly, remember that this is not going to be something that gets fixed in one problem-solving conversation. Be patient. Your child is learning. You are learning too as you deal with these hard situations.

This Halloween, don’t just try to limit how much candy your child eats. Think about how your approach affects your child’s relationship with food. Think about their independence. Think about whether they trust you. The goal is to raise kids who can make good choices. We also want them to enjoy the celebrations that make childhood special.

Note: Links to Amazon are affiliate links.

Turn Daily Power Struggles Into Collaboration

Do your Halloween candy battles also show up as arguments about bedtime, screen time, chores, and every other rule your child pushes back on? You’ve tried everything – rewards, consequences, pleading, getting tough – but the same patterns keep repeating.

You already see how collaboration works better than control. Now learn how to create that calm partnership on every topic where your child tests limits.

The Setting Loving (& Effective) Limits workshop gives you the exact tools to make this shift. You’ll learn how to move from constant struggles and nagging to genuine partnership with your child – without bribes, threats, or giving in.

Sign up for the workshop today!

Frequently Asked Questions About Halloween Candy

1. Why is Halloween candy so addictive?

Research shows kids do like sweet things more than grown-ups – and that built-in preference gets amped up even higher with exposure to sweet foods. However, calling sugar “addictive” creates urgency that isn’t really backed by research. The real issue is that restriction often creates obsession and sneaking behaviors.

2. What happens if you eat too much candy in one day?

The effects are usually milder than parents expect. Dr. Michael Goran’s research shows fructose gets processed by the liver and can cause inflammation. But observable symptoms typically include constipation and energy spikes followed by crashes. Controlled studies often find that these energy spikes are much lower than parents might imagine (in one study, researchers had to create a new category of movement to distinguish between baseline and slightly above baseline when kids ate a sugary breakfast).

3. How much is too much Halloween candy?

Instead of focusing on exact amounts, watch for signs your approach isn’t working. This may include sneaking and hiding candy, constant arguments about treats, or going overboard at parties. These red flags show your restrictions may be creating the problems you’re trying to avoid.

4. Should I let my kids eat all their Halloween candy?

Most children benefit when we focus more on their relationship with food than the specifics of what they’re eating. You may find that allowing more freedom reduces your child’s sense of ‘not enough-ness’ as well as fights over food, which keeps interactions around food more positive. Overall, we’re trying to help kids navigate their own food intake rather than controlling it ourselves.

5. How to limit kids’ Halloween candy?

Use collaborative problem-solving instead of imposing strict rules. Understand everyone’s needs. Generate solutions together and create specific agreements your child helps make. Plan for unexpected scenarios, and adjust as needed. Children are more likely to follow agreements they helped create.

6. What are the signs of too much sugar in your body?

Help children connect food choices to how they feel: “You had ice cream and didn’t want dinner, but now you’re hungry again.” Explain sugar’s effects without shame: “This gives you energy fast, then it wears off.” This builds internal awareness rather than reliance on external rules.

7. How to get rid of excess Halloween candy?

You might feel tempted to just throw excess candy away, but this may undermine trust in your relationship with your child. They may also think it’s unfair because their friends get candy and they don’t. When we create scarcity around highly palatable foods like candy, kids may respond by wanting it more. Restricting their access to candy when they’re young may not necessarily lead to the healthy eating habits you want to instill. You may find that kids eat a wider variety of foods when we back off from controlling what’s available to them.

8. Is Halloween candy healthy?

Halloween candy isn’t nutritious, but the social and emotional aspects matter too. Dr. Karen Throsby notes that food is “an important site of pleasure,” tied to celebration and connection. Focus on overall nutrition patterns while allowing children to participate fully in cultural traditions without shame.

9. What is a healthy alternative to Halloween candy?

Don’t focus on replacing Halloween traditions. Focus on building a healthy relationship with all foods. Emphasize increasing fiber, protein, and vegetables year-round while reducing sugar gradually. Remember this is an ongoing journey.

References

Brown, R., & Ogden, J. (2004). Children’s eating attitudes and behaviour: a study of the modelling and control theories of parental influence. Health education research, 19(3), 261–271. https://doi.org/10.1093/her/cyg040

Guideline: Sugars intake for adults and children. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2015. Hu F. B. (2002). Dietary pattern analysis: a new direction in nutritional epidemiology. Current opinion in lipidology, 13(1), 3–9. https://doi.org/10.1097/00041433-200202000-00002

Ludwig D. S. (2002). The glycemic index: physiological mechanisms relating to obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease. JAMA, 287(18), 2414–2423. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.287.18.2414

Lumanlan, J. (2022, January 9). Sugar Rush with Dr. Karen Throsby. Your Parenting Mojo. https://yourparentingmojo.com/captivate-podcast/sugarrush/

Lumanlan, J. (2021, October 3). How to Sugarproof your kids with Dr. Michael Goran. Your Parenting Mojo. https://yourparentingmojo.com/captivate-podcast/sugarproof/

Lumanlan, J. (2021, August 15). Division of Responsibility with Ellyn Satter. Your Parenting Mojo. https://yourparentingmojo.com/captivate-podcast/dor/

Lumanlan, J. (2019, July 7). Using nonviolent communication to parent more peacefully. Your Parenting Mojo. https://yourparentingmojo.com/captivate-podcast/nvc/

Lumanlan, J. (2019, May 5). SYPM002: Sugar! with Rose Amanda. Your Parenting Mojo. https://yourparentingmojo.com/captivate-podcast/roseamanda/

Lumanlan, J. (2016, October 10). Help! My toddler won’t eat vegetables. Your Parenting Mojo. https://yourparentingmojo.com/captivate-podcast/007-help-toddler-wont-eat-vegetables/

Patrick, H., & Nicklas, T. A. (2005). A review of family and social determinants of children’s eating patterns and diet quality. Journal of the American College of Nutrition, 24(2), 83–92. https://doi.org/10.1080/07315724.2005.10719448

Wolraich, M. L., Wilson, D. B., & White, J. W. (1995). The effect of sugar on behavior or cognition in children. A meta-analysis. JAMA, 274(20), 1617–1621. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.1995.03530200053037