Intergenerational Trauma: How to Break & Heal the Anger Trigger Cycle

Key Takeaway

- Intergenerational trauma occurs when effects of past experiences pass to children and grandchildren, even when they never experienced the original traumatic events themselves.

- Parents may react intensely to small behaviors because trauma survivors often struggle with emotion regulation, especially during stressful parenting moments. Strong reactions happen when children unconsciously remind parents of their own childhood experiences, activating old emotions and survival responses – this is called being “triggered.”

- Being “triggered” is a clinical term that describes when trauma survivors experience intense reactions because present situations remind them of past traumatic events. Parents without trauma histories may experience emotional overwhelm or “flooding,” but this is different from being triggered.

- Trauma shows up today when parents blame their child – or themselves – rather than recognizing deeper patterns from their past are at play.

- Breaking cycles starts with understanding your triggers and pausing before reacting, creating space between past wounds and present responses.

- Processing your story in safe environments helps organize traumatic memories and prevents both complete silence and constant rehashing from harming relationships.

- Healing involves keeping focus on your child’s actual needs rather than trying to rewrite your own childhood through your parenting decisions.

My-Linh Le grew up in San José watching her parents explode over small mistakes – when she forgot her backpack in first grade, her mother “kicked that thing across the room and hit the wall so hard it terrified me.” When her sister messed up dinner, her father threw dishes at the wall. The house was filled with an unpredictable rage that left Le lying awake at night, anxious about what mistakes she might make the next day.

As a child, Le assumed all Vietnamese families were like this. But years later, as an adult, she realized something that shook her. During a phone call with her boyfriend, when he didn’t do something she expected by a certain time, rage “just suddenly came out of nowhere, just like totally bubbled up within me.” She wanted to throw the phone across the room. “It was this really depressing moment of realizing that I’m just like my mother,” she said.

Despite spending her childhood learning to suppress her anger to avoid setting her parents off, their trauma had somehow passed to her too. Her father’s first wife and son had drowned when their boat sank trying to reach America. Her mother had left a daughter behind in Vietnam, too afraid that the girl’s kicking and screaming would mean their escape would be discovered. These losses – never discussed, barely acknowledged – had shaped a family’s emotional landscape and passed their effects to the next generation.

I realized that trauma doesn’t just affect the people who directly experience it. It can ripple through generations, showing up in unexpected ways in children and grandchildren who never experienced the original events. This blog post draws on my conversation with Dr. Rebecca Babcock Fenerci, a licensed clinical psychologist from Stone Hill College whose research focuses on intergenerational trauma resulting from family-based trauma.

Based on the insights from our conversation, this blog post will explore how intergenerational trauma can show up in parenting and practical strategies to break the cycle of trauma.

What Is Intergenerational Trauma

The definition of intergenerational trauma goes beyond what many people initially think.

Dr. Fenerci explains that when we first consider intergenerational trauma, we might think about trauma being perpetuated across generations – parents experienced some type of trauma, whether being a victim of abuse or neglect, and then their own child has similar experiences.

But intergenerational trauma encompasses much more than direct repetition. The definition also includes the increased risk these children have for experiencing the consequences of that trauma, such as post-traumatic stress disorder, mood disorders, behavioral problems, and disrupted attachment.

Dr. Fenerci gives this example:

“A child whose parent survived physical abuse growing up may be at risk if that child also experienced physical abuse. But the child might also be at increased risk for certain mood disorders or behavior problems or disrupted attachment, altered cortisol or stress-response system functioning.”

This means trauma transmission can happen even when the specific traumatic events aren’t repeated. The effects of trauma like the altered stress responses, emotional patterns, and relationship difficulties can pass to the next generation.

Why Do People React So Differently to Trauma

I was surprised to learn how differently people may react to traumatic circumstances. Studies on coping with trauma have looked at Holocaust survivors and children of Vietnam War veterans. Even within these groups, the effects were completely different for different people. Some people experience truly horrific events, and go on to lead fulfilled lives. Others see what we might think of as less overwhelming events, but they are profoundly impacted by them.

Dr. Fenerci explains why this happens, using the diathesis-stress model. This shows that our genes and stressful events work together. They shape what happens to us.

“If you’re thinking about the results of trauma and its consequences, whether it’s increased results in psychopathology or developments of mental illness or post-traumatic stress disorder or other negative consequences, it really depends a lot on certain risk factors that may run in a particular family.”

This includes genetics, but also epigenetics – how our experiences can actually change which genes are turned on or off.

“It’s an ongoing interaction between genetics which may result in a certain predisposition or personality,” she notes.

Even siblings who grew up in the same family and share half their genes can have very different outcomes.

The severity and chronicity of trauma also matter. As Dr. Fenerci puts it:

“The more chronic or severe the trauma – such as the Holocaust, that’s exceptionally severe, exceptionally chronic, the more likely it is that the trauma is going to have an impact on a large percent of the population that has endured that.”

How the Brain Processes Trauma

Understanding how trauma works in the brain helps explain why it can affect us and our children for years. The brain handles trauma differently than regular memories.

When an event happens that we find traumatic, our fight or flight response kicks in. Our body gets flooded with stress hormones. When this happens too much, especially with family trauma, it can cause two things. We might have very vivid memories that keep coming back. Or we might forget the trauma completely.

During traumatic events, the limbic system in our brain works extra hard to keep us safe. But the frontal lobe which helps us think clearly and make sense of things shuts down. This is the part of the brain that helps us organize our memories and understand what happened to us.

This survival mechanism becomes problematic when trauma isn’t discussed. When a trauma isn’t talked about, the survivor is never able to process and make sense of the events.

The Extremes: Too Much Silence vs. Too Much Sharing

Through listener stories, we see both ends of the spectrum when it comes to family trauma and communication. Some never talk about it at all. Others talk about it all the time. Both ways can cause problems.

The Danger of Complete Silence

One pattern involves never discussing traumatic experiences. Many Japanese Americans virtually never mentioned their experiences in internment camps during World War II. This left lasting effects on their children.

When we’re traumatized by something, it affects us in many different ways. If we never get to make sense of what happened, those effects keep playing out in our relationships and everyday experiences.

The Problem with Constant Rehashing

On the opposite extreme, one listener shared an example of family trauma. Her grandfather had been so abusive that he once lined up his wife and children at gunpoint, planning to kill them all before killing himself. Only when the mother came out of the bathroom and yelled for him to stop did he drop the gun, allowing the grandmother to sneak all the children out of the house that night.

The four older daughters developed various addiction issues throughout their lives. But there was something else going on:

“Every time they would get together as a family, they would rehash all of their memories of the abuse in absolutely excruciating detail.”

Despite this constant discussion, the listener, who grew up in an otherwise loving home, found herself very fearful and couldn’t understand why.

This constant retelling can create vicarious traumatization. When we hear about a traumatic event experienced by someone we love, it can make us upset.

6 Ways Trauma Shows Up in Parenting

Parenting after trauma presents unique challenges. Here are several specific mechanisms through which trauma impacts the next generation.

How trauma shows up in parenting #1: Strong emotional reactions

Parents who experienced trauma may get furious over small things – not just annoyed, but experiencing the same fight-or-flight response they had during their original traumatic experiences.

Being “triggered” is a clinical term that describes when something in the present unconsciously reminds a trauma survivor of past traumatic events. Their brain responds as if the original danger is happening again, even when the actual situation is minor.

This might happen when their child asks for something over and over, or when they get interrupted while talking.

This connects to a powerful story from podcast listener Katie. She was adopted from the USSR after her alcoholic, abusive parents spent time in prison. Katie works hard with medication and therapy to build a strong bond with her son. But she knows she gets angry very quickly. Simple things set her off. She reacts quickly and harshly when her son repeats things over and over, and when he does something she asks him not to do.

It’s important to note that not every strong parenting reaction qualifies as being “triggered.” Parents without trauma histories may experience intense emotions or “flooding” when overwhelmed, but this is different from the trauma-based activation that defines triggering.

How trauma shows up in parenting #2: Children as trauma reminders

A parent’s own child may actually serve as a trauma reminder. This may be conscious or unconscious. When children are traumatized by their caregivers or other family members, it can disrupt their ability to form healthy attachments.

When people who were hurt by caregivers become parents themselves, they’re now on the other side of that attachment relationship. Being close to your child can remind you of how your own parents treated you when you were a kid.

If you went through something hard or hurtful back then, those old emotions might come back. This happens even if you haven’t thought it through or talked about it. You might not even realize it’s happening. Sometimes, those emotions can affect how you treat your own child, even though you don’t mean for this to happen.

How trauma shows up in parenting #3: When we think our reaction about our kids, but really it’s about our past

Sometimes parents don’t realize their intense reactions are related to their past experiences – especially if things have been ‘fine’ up to the point when they had children. They might think, “My child is making me angry” rather than recognizing deeper patterns at play.

This is what psychologist John Briere calls ‘source attribution errors.’ When parents don’t understand where their upset emotions come from, they blame the wrong thing. They might blame their child or themselves. So even when their child acts normally for their age, the parent gets triggered easily.

The problem gets worse because we often believe everything we think is true. When we think “My child doesn’t respect me” or “I’m a terrible parent”, these thoughts seem like facts. But our explanation is just one way to make sense of what’s happening. There could be many other explanations. A child might jump on the couch even when you’ve told them not to because they’re deliberately trying to irritate you…or because they’ve had a hard day and they’re trying to get your attention to connect with you.

When you can step back from your automatic thoughts, you might discover your child isn’t trying to disrespect or annoy you at all. They might be trying to meet their own needs in the only way they know how. When we understand what need our child is trying to meet through their behavior that we find difficult, we often find strategies to meet both of our needs.

How trauma shows up in parenting #4: Disorganized memory and trauma-related thoughts

Dr. Fenerci studied disorganized memory, which happens when the person who had a traumatic experience hasn’t processed or understood what happened. She found that mothers who had experienced abuse as children were more likely to have toddlers who seemed sad, withdrawn, or anxious.

She also studied specific thoughts and emotions that can stick around after traumatic experiences – things like shame, anger, fear, self-blame, and feeling cut off from others. She wanted to understand how these might affect parenting relationships. One key finding stood out: when mothers carried a lot of shame from their past, their toddlers were more likely to struggle with mood and behavior issues.

How trauma shows up in parenting #5: Difficulty regulating emotions

Children learn how to manage their own emotions by observing and interacting with their parents.

But trauma survivors often have trouble with emotion regulation themselves, especially when dealing with challenging or stressful situations. Parenting is already tough, and if your child is acting out or pushing your buttons, it’s even harder. It can be difficult to teach your child how to manage their emotions when you’re struggling with your own.

This challenge doesn’t just affect your relationship with your children. It impacts your whole family system, including your relationship with your partner. When one parent gets triggered or flooded, it can trigger the other parent too. The stress spreads through the family like ripples in a pond.

How trauma shows up in parenting #6: Sense of loss and unmet needs

When parents didn’t get what they needed as children, it can show up in confusing ways with their own kids. Sometimes trauma survivors unconsciously expect their children to meet needs that weren’t met in their own childhood. This flips the relationship – suddenly the parent’s needs become more important than the child’s.

It might look like this: A child reaches out for connection, but their parent gets angry instead of responding warmly. Why? Because that parent might remember their own childhood, when they reached out for connection their parent reacted angrily. Without realizing it, they’re repeating the pattern.

But there’s another layer that makes this even harder. When parents start giving their children the love and attention they themselves never received, it can bring up painful awareness of what they missed. This puts parents in a tough spot. They’re trying to heal their own wounds while also showing up for a child who depends on them completely.

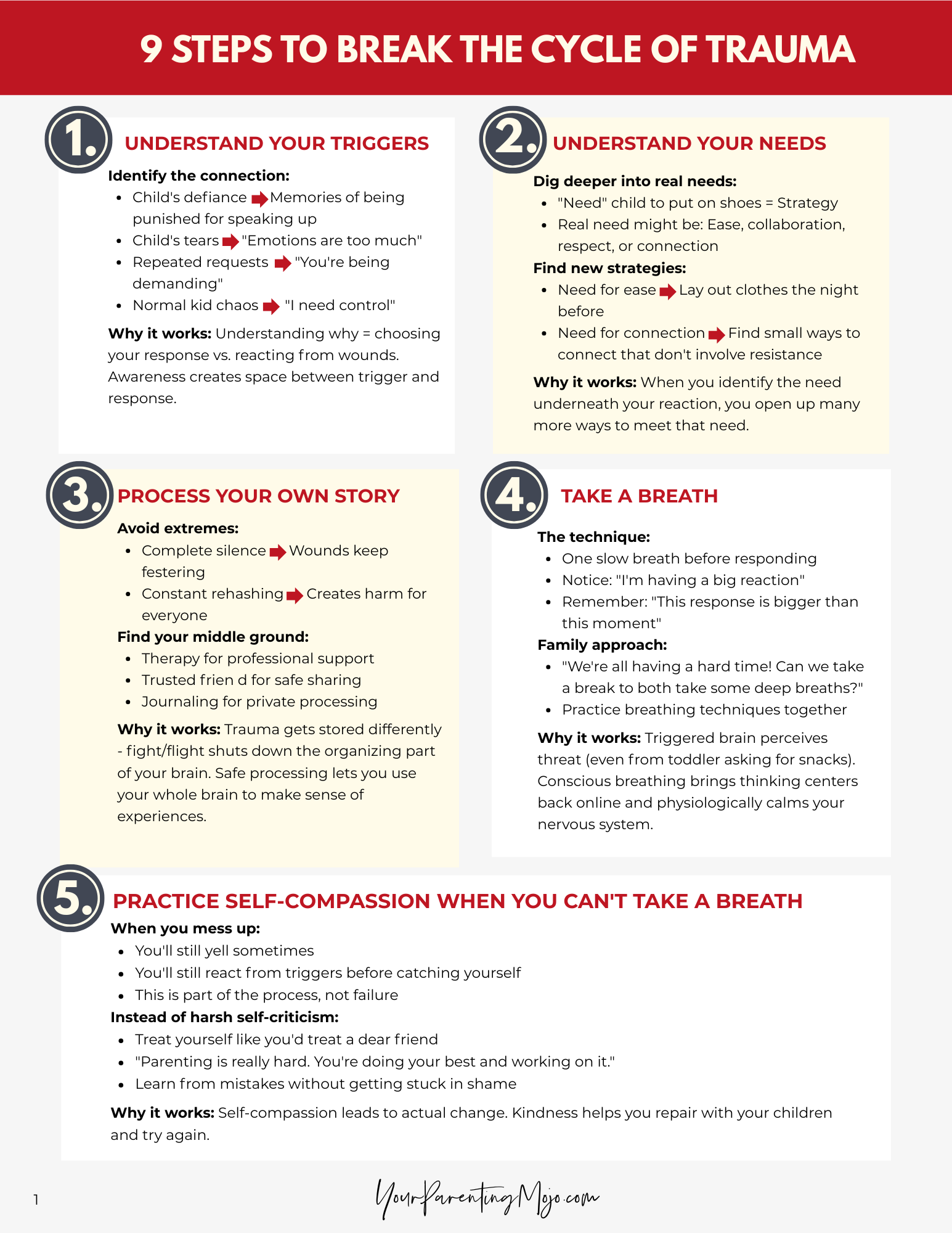

9 Steps to Break the Cycle of Trauma

Click here to download the 9 Steps to Break the Cycle of Trauma

How to break the cycle of trauma #1: Understand your triggers

Common triggers often relate to past experiences in ways we don’t immediately recognize. Start by looking closely at what specifically sets off your sudden anger.

When a child’s action triggers us, there’s usually a thread connecting it to something from our own childhood. Maybe their defiance reminds us of times we were punished for speaking up. Or their tears bring back memories of being told our emotions were “too much”.

This awareness doesn’t make the triggers disappear overnight. But when we understand why we’re reacting so strongly, we may be able to create space between the trigger and our response. In that space, we can choose how to respond rather than just reacting from our past wounds.

How to break the cycle of trauma #2: Understand your needs

Understanding your triggers is just the first step. You also want to understand what needs you’re trying to meet when you get triggered.

Often we think we ‘need’ our child to put on their shoes or brush their teeth, but these aren’t actually needs – they’re strategies. Your real needs might be for ease, collaboration, or connection.

When you can identify the need underneath your reaction, you open up many more ways to meet that need. If your need is for ease and your child won’t get dressed, maybe you can lay out clothes the night before or let them pick between two outfits. If your need is for connection and they’re pushing you away, maybe you can find a small way to connect that doesn’t involve the thing they’re resisting.

How to break the cycle of trauma #3: Process your own story

As we’ve discussed earlier, too much silence and too much sharing can do more harm. Avoiding the topic altogether can keep old wounds festering, but so can rehashing them in exhaustive detail with anyone who will listen. Aim for a middle ground, whether that’s with a therapist, a trusted friend, or in a journal, where you can tell your story in a way that helps you make meaning of it.

Trauma gets stored differently in our brains. When our fight-or-flight system is activated, the part of our brain that helps us organize and make sense of experiences gets shut down. That’s why revisiting these experiences in a safe, supportive environment can be so helpful because it allows us to use our whole brain to process what happened.

How to break the cycle of trauma #4: Take a breath

When you notice intense anger or other strong emotions, try taking one conscious breath before responding. This gives your brain’s thinking centers a chance to come back online and helps you respond more thoughtfully.

Understanding where these big emotions come from can help make this strategy even more effective. When we’re triggered, our body is responding to something it perceives as a threat – even when that threat is actually just our toddler asking for a snack for the fifth time. Our brain doesn’t always distinguish between real danger and reminders of past pain.

You can also practice family-wide breathing practice. Parents can model these techniques for children and suggest doing it together: “We’re all having a hard time! Is it okay if we take a break to both take some deep breaths?”

This approach has several benefits. Not only does that give us the moment to think, but it also physiologically calms our system down because when we experience anger or other intense emotions, our sympathetic nervous system gets activated, so to be able to calm that system down gives us some time to be able to think things through.

How to break the cycle of trauma #5: When you can’t take a breath, practice self-compassion

You won’t be able to do this perfectly every time. Sometimes you’ll still yell. Sometimes you’ll still react from your triggers before you can catch yourself. This can be really discouraging.

When we mess up, we often beat ourselves up about it. We think things like “I’m a terrible parent” or “I should know better by now”. But this harsh self-criticism actually makes it harder to change our patterns.

Instead, try treating yourself with the same compassion you’d offer a dear friend. If your friend told you they yelled at their child, you probably wouldn’t say “You’re awful and you’ll never get better at this.” You’d likely say something like “Parenting is really hard. You’re doing your best and you’re working on it.”

That same gentle approach with ourselves is much more likely to lead to actual change. When we’re kind to ourselves about our mistakes, we can learn from them without getting stuck in shame. We can repair with our children and try again tomorrow.

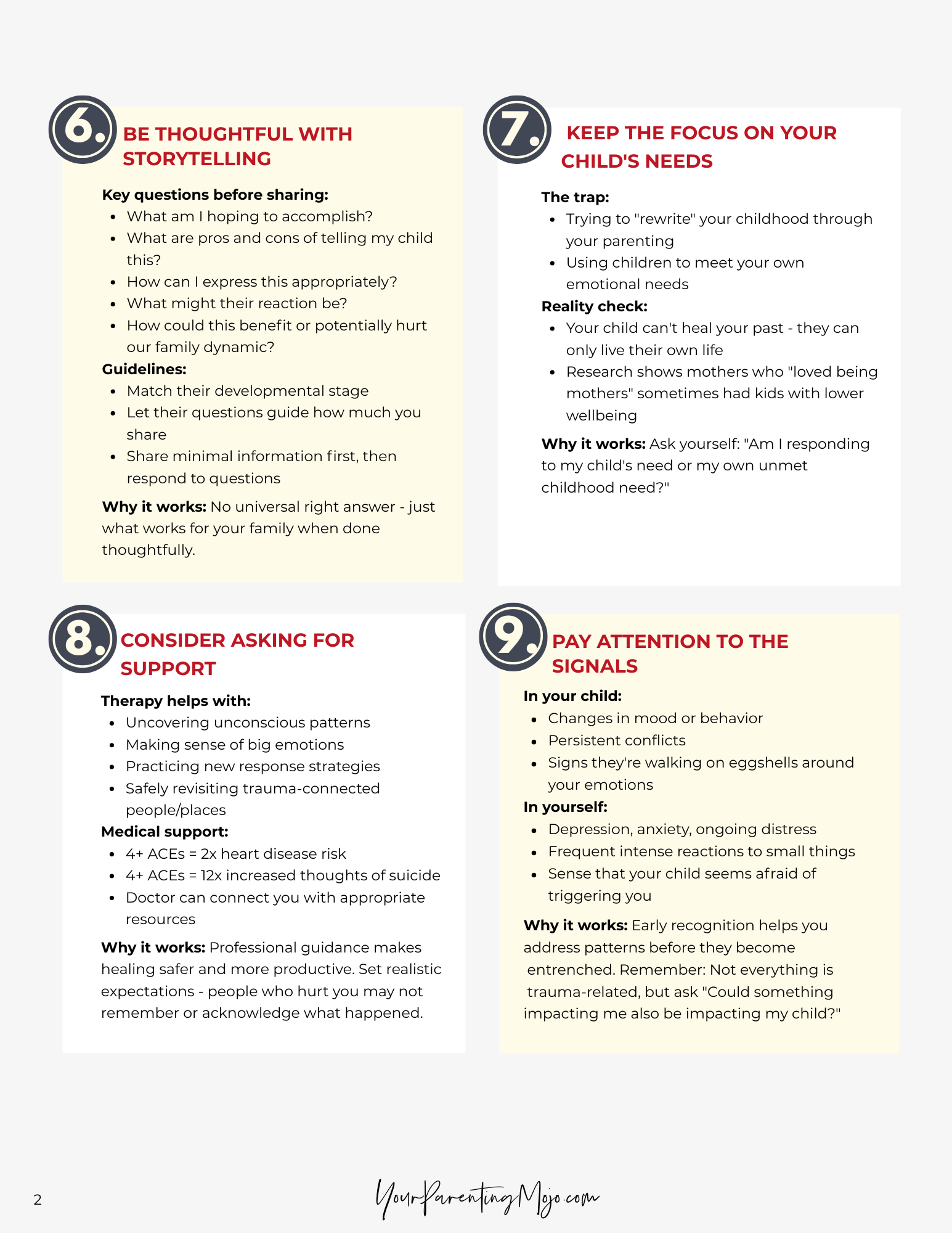

How to break the cycle of trauma #6: Be thoughtful with storytelling

If you choose to share aspects of your past with your child, keep their developmental stage in mind and let their questions guide how much you say. The goal is to not overwhelm them with details they can’t yet process.

Consider what you’re hoping to accomplish by sharing:

- What are the pros and cons of saying this to my child?

- How would I like to express this to them?

- What could their reaction be to this situation and what is the purpose of telling them?

- How could this potentially benefit our family?

- What could it potentially hurt the family dynamic in some way?”

There’s no universal right answer – just what works for your family. By sharing minimal information and then responding to their questions, you’re less likely to share information they aren’t ready for yet.

How to break the cycle of trauma #7: Keep the focus on your child’s needs

It’s understandable to want to “rewrite” our own childhoods through our parenting, but that can easily shift the focus from the child’s needs to our own unmet ones. Our children can’t heal our past – they can only live their own lives, with our support.

Dr. Fenerci found something surprising in her research: mothers who reported “loving being mothers” sometimes had children with lower social-emotional wellbeing. Her hypothesis was that these mothers might be unconsciously using their children to meet their own emotional needs rather than focusing on what their kids actually needed.

How to break the cycle of trauma #8: Consider asking for support in navigating your traumatic experiences

Therapy can be an invaluable tool for uncovering unconscious patterns, making sense of big emotions, and practicing new ways of responding. And if you ever consider revisiting the people or places connected to your trauma, having professional guidance can make that process safer and more productive.

Remember that the people who hurt us might not remember things the way we do or they might not be willing to acknowledge what happened. Going in with realistic expectations and support can help protect you from additional harm.

You might also consider talking with your healthcare provider about your experiences. Research on Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) shows that early trauma can affect not just our mental health, but our physical health too. People with four or more ACEs have twice the risk for heart disease and over 12 times the risk for thoughts of suicide. Your doctor can help you understand how your experiences might be impacting your overall health and connect you with appropriate resources.

How to break the cycle of trauma #9: Pay attention to the signals

Changes in your child’s mood or behavior, persistent conflicts, or experiences of depression, anxiety, or distress in yourself are all important signs. Sometimes the “problem” we see in our child is actually a sign that something deeper is going on in the family dynamic.

This doesn’t mean everything is your fault. Kids go through normal developmental phases, and plenty of challenges have nothing to do with our past trauma. But it’s worth asking: Could something that’s impacting me also be impacting my child?

Going Deeper: Taming Your Triggers

These nine steps can make a real difference. But if you’re finding that intense reactions are happening frequently, if you’re regularly “seeing red” over small things, or if you notice your child starting to walk on eggshells around your emotions, you might benefit from more targeted support around triggers specifically.

When we’re triggered, our brain’s alarm system takes over. The part that can think clearly and make good decisions goes offline. That’s why simply telling ourselves to “calm down” rarely works because we need different tools.

In my Taming Your Triggers workshop, we dig deeper into understanding what’s happening in your brain and body when you get triggered, and practice specific strategies for:

- Catching yourself before the trigger takes full hold

- Calming your nervous system in the moment

- Responding to your child from a place of connection rather than reaction

- Having conversations after big reactions that actually bring you closer together

Many parents tell me this work has transformed not just their parenting, but their relationships with their partners and even their own sense of self. When you can stay present with your child even in challenging moments, both of you benefit.

K.D., a parent who took the workshop, shared:

“I’ve been determined to break the generational trauma with my own children while holding my triggers like an inevitable nuisance at best and as only human when I lost it and react. It’s so incredibly freeing to consider that possibility that I could lay down those chains all together.

The Taming Your Triggers workshop was a clear, concise and actionable path forward. The workshop gave me very clear steps to take toward being the mother I aspire to be by helping me heal my own hurt. Since the workshop I’m more patient and have greater capacity.”

Breaking the cycle comes down to becoming aware of what you’re carrying, and choosing to respond with intention instead of reaction. When you pause, reflect, and respond differently, you’re building new patterns that your children will carry forward into their own lives.

Ready to learn how to tame your triggers and break the cycle of trauma?

Click the banner to learn more!

Final Thoughts

Breaking cycles of intergenerational trauma means making intentional choices to respond in ways that are different from the patterns you inherited. This work takes time and patience with yourself.

You might still get triggered sometimes. You might catch yourself reacting in ways that remind you of your own childhood. That’s part of being human. What matters is that you’re aware, you’re trying, and you’re willing to repair when things go sideways.

The trauma you experienced wasn’t your fault, but the healing you do now is your gift – to yourself, to your children, and to the generations that will come after them.

This isn’t easy work, but it’s some of the most important work you’ll ever do. And you don’t have to do it alone. Whether through therapy, supportive community, or resources like the Taming Your Triggers workshop, help is available when you’re ready to take the next step.

The chains of trauma that were passed down to you don’t have to be the legacy you leave behind. You have the power to transform pain into wisdom, reactivity into responsiveness, and old wounds into new possibilities for connection. Your children, and their children, will benefit from the courage you show today.

Frequently Asked Questions About Intergenerational Trauma

1. What is intergenerational trauma?

Intergenerational trauma goes beyond direct repetition of traumatic events. It includes the increased risk children have for experiencing consequences of their parents’ trauma, such as mood disorders, behavioral problems, and disrupted attachment. Even when you don’t experience the exact same events that your parents did, effects like altered stress responses, emotional patterns, and relationship difficulties can pass down to you (and potentially to your kids as well).

2. Why do people react so differently to trauma?

People’s reactions depend on the interaction between genetics, epigenetics, and environmental factors. This is called the ‘diathesis-stress model.’ Even siblings in the same family can have very different outcomes because of genetic predisposition, personality differences, and how experiences change which genes are turned on or off. The severity and chronicity of trauma also affect how many people will be impacted.

3. How does trauma affect the brain and memory?

During trauma, the fight-or-flight response floods the body with stress hormones. The limbic system works overtime for safety, but the frontal lobe that helps organize memories and make sense of experiences shuts down. This creates either vivid, intrusive memories or complete memory gaps. When trauma isn’t processed, the survivor never gets to organize these experiences in a coherent way.

4. How does trauma show up in parenting?

Trauma appears through strong emotional reactions to small triggers, children serving as trauma reminders, source attribution errors where parents blame the wrong cause for their emotions, disorganized memories affecting parent-child relationships, difficulty regulating emotions, and unconsciously expecting children to meet needs that weren’t met in the parent’s own childhood, flipping the relationship dynamic.

5. How can parents break the cycle of trauma?

Start by understanding your triggers and the needs behind them. Process your story in safe environments, avoiding both complete silence and constant rehashing. Take conscious breaths when triggered to help your thinking brain come back online. Keep focus on your child’s actual needs rather than trying to rewrite your own childhood through parenting decisions.

6. When should parents seek professional support?

Consider therapy when intense reactions happen frequently, when you’re “seeing red” over small things, or when your child starts walking on eggshells around your emotions. Professional guidance is especially valuable when revisiting people or places connected to trauma. Changes in your child’s mood, persistent conflicts, or your own experiences of depression and anxiety are worth addressing.

7. How should parents share their trauma story with children?

Be thoughtful about developmental appropriateness and let your child’s questions guide how much you share. Consider what you hope to accomplish, potential benefits and risks, and how sharing might affect family dynamics. The goal is to help them understand their own experiences with you, without burdening them with adult emotional work.

References

Babcock Fenerci, R. L., Chu, A. T., & DePrince, A. P. (2016). Intergenerational Transmission of Trauma-Related Distress: Maternal Betrayal Trauma, Parenting Attitudes, and Behaviors. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma, 25(4), 382–399. https://doi.org/10.1080/10926771.2015.1129655

Bonanno G. A. (2004). Loss, trauma, and human resilience: have we underestimated the human capacity to thrive after extremely aversive events?. The American psychologist, 59(1), 20–28. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.59.1.20

Briere, J. (2010). A summary of self-trauma model applications for severe trauma: Treating the torture survivor. Center for Victims of Torture. https://healtorture.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/A_Summary_of_Self-Trauma_Model_Applications_for_Severe_Trauma_Treating_the_Torture_Survivor.pdf

Dembosky, A. (2025, May 1). Just like my mother: How we inherit our parents’ traits and tragedies. KQED. https://www.kqed.org/news/11616586/just-like-my-mother-how-we-inherit-our-parents-traits-and-tragedies

Fenerci, R. L. B., & DePrince, A. P. (2018). Intergenerational Transmission of Trauma: Maternal Trauma-Related Cognitions and Toddler Symptoms. Child maltreatment, 23(2), 126–136. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077559517737376

Fonagy, P., Steele, M., Steele, H., Higgitt, A., & Target, M. (1994). The Emanuel Miller Memorial Lecture 1992. The theory and practice of resilience. Journal of child psychology and psychiatry, and allied disciplines, 35(2), 231–257. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.1994.tb01160.x

Fraiberg, S., Adelson, E., & Shapiro, V. (1975). Ghosts in the nursery. A psychoanalytic approach to the problems of impaired infant-mother relationships. Journal of the American Academy of Child Psychiatry, 14(3), 387–421. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0002-7138(09)61442-4

Lumanlan, J. (2024, October 6). Where emotions come from (and why it matters) Part 1. Your Parenting Mojo. https://yourparentingmojo.com/captivate-podcast/emotionspart1/

Lumanlan, J (2024, February 2). The Real Reasons You Feel Triggered by Your Child’s Behavior. Psychology Today. https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/parenting-beyond-power/202402/the-real-reasons-you-feel-triggered-by-your-childs-behavior

Lumanlan, J. (2024, January 28). How to Heal from Adverse Childhood Experiences with Dr. Nadine Burke Harris and Jackie Thu-Huong Wong. Your Parenting Mojo. https://yourparentingmojo.com/captivate-podcast/aces/

Lumanlan, J. (2023, October 8). Regulating for the kids…and for your marriage. Your Parenting Mojo. https://yourparentingmojo.com/captivate-podcast/foryourmarriage/

Lumanlan, J. (2023, October 1). You don’t have to believe everything you think. Your Parenting Mojo. https://yourparentingmojo.com/captivate-podcast/thoughts/

Lumanlan, J. (2022, February 20). Why are you always so angry?. Your Parenting Mojo. https://yourparentingmojo.com/captivate-podcast/iris/

Lumanlan, J. (2021, July 25). The Body Keeps The Score with Dr. Bessel van der Kolk. Your Parenting Mojo. https://yourparentingmojo.com/captivate-podcast/thebodykeepsthescore/

Lumanlan, J. (2021, February 21). Introduction to mindfulness and meditation with Diana Winston. Your Parenting Mojo. https://yourparentingmojo.com/captivate-podcast/mindfulness/

Lumanlan, J. (2020, October 18). Self-Compassion for Parents. Your Parenting Mojo. https://yourparentingmojo.com/captivate-podcast/selfcompassion/

Lumanlan, J. (2018, July 22). Reducing the impact of intergenerational trauma. Your Parenting Mojo. https://yourparentingmojo.com/captivate-podcast/intergenerationaltrauma/

Lumanlan, J. (2018, May 7). How family storytelling can help you to develop closer relationships and overcome struggles. Your Parenting Mojo. https://yourparentingmojo.com/captivate-podcast/familystorytelling/

Lumanlan, J. (n.d.-a). Identifying your child’s wants quiz. Your Parenting Mojo. https://yourparentingmojo.com/quiz

Lumanlan, J. (n.d.-b). Needs list. Your Parenting Mojo. https://yourparentingmojo.com/needs/

Lyons-Ruth, K., & Block, D. (1996). The disturbed caregiving system: Relations among childhood trauma, maternal caregiving, and infant affect and attachment. Infant Mental Health Journal, 17(3), 257–275. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1097-0355(199623)17:3<257::AID-IMHJ5>3.0.CO;2-L

Main, M., Kaplan, N., & Cassidy, J. (1985). Security in infancy, childhood, and adulthood: A move to the level of representation. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 50(1-2), 66–104. https://doi.org/10.2307/3333827

McEwen B. S. (2007). Physiology and neurobiology of stress and adaptation: central role of the brain. Physiological reviews, 87(3), 873–904. https://doi.org/10.1152/physrev.00041.2006

Minuchin, S. (1974). Families & family therapy. Harvard U. Press.

Monroe, S. M., & Simons, A. D. (1991). Diathesis-stress theories in the context of life stress research: implications for the depressive disorders. Psychological bulletin, 110(3), 406–425. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.110.3.406

Morelen, D., Shaffer, A., & Suveg, C. (2016). Maternal emotion regulation: Links to emotion parenting and child emotion regulation. Journal of Family Issues, 37(13), 1891–1916. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X14546720

Nagata, D. K. (1991). Transgenerational impact of the Japanese-American internment: Clinical issues in working with children of former internees. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 28(1), 121–128. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-3204.28.1.121

Schauer, M., Neuner, F., & Elbert, T. (2011). Narrative exposure therapy: A short-term treatment for traumatic stress disorders (2nd rev. and expanded ed.). Hogrefe Publishing.

Schechter, D. S., & Willheim, E. (2009). Disturbances of attachment and parental psychopathology in early childhood. Child and adolescent psychiatric clinics of North America, 18(3), 665–686. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chc.2009.03.001

Willcott-Benoit, W., & Cummings, J. A. (2024). Vicarious Growth, Traumatization, and Event Centrality in Loved Ones Indirectly Exposed to Interpersonal Trauma: A Scoping Review. Trauma, violence & abuse, 25(5), 3643–3661. https://doi.org/10.1177/15248380241255736

Yehuda, R., & Lehrner, A. (2018). Intergenerational transmission of trauma effects: putative role of epigenetic mechanisms. World psychiatry : official journal of the World Psychiatric Association (WPA), 17(3), 243–257. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20568

Yehuda, R., Daskalakis, N. P., Lehrner, A., Desarnaud, F., Bader, H. N., Makotkine, I., Flory, J. D., Bierer, L. M., & Meaney, M. J. (2014). Influences of maternal and paternal PTSD on epigenetic regulation of the glucocorticoid receptor gene in Holocaust survivor offspring. The American journal of psychiatry, 171(8), 872–880. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2014.13121571